Over the past few years, I've become known as the shoulder guy on the list of T-Nation contributors.

Nobody ever really asked why this became an area of interest for me; all they care about is how to recover from impingement, labral tears, bicipital tendonosis, AC joint sprains, and the occasional accidental amputation. (I usually recommend a bottle of whiskey, some duct tape, and a glue gun for that last one.)

Truth be told, my shoulders have taken a beating during my career as a competitive athlete, so I've got a pretty good frame of reference. Would you believe that this powerlifter was an all-state tennis player in high school?

Let's just say that my kick serve wasn't exactly conducive to shoulder health, so before I ever picked up a weight, I'd lost a chance to play in college due to internal impingement – a hypermobility condition that led to a partial thickness tear of my right supraspinatus and enough bone spurs to sink a battleship.

Surgery was scheduled for December of 2003, but rather than just wait for the 'scope, I buckled down, read everything I could find, and experimented in my training to find what I could and couldn't do in an attempt to avoid the surgery.

The end result? I canceled the surgery in October of 2003 and took up powerlifting, where I'm on the brink of bench pressing 400 pounds at a body weight of 165.

Unfortunately, it wasn't always smooth sailing between 2003 and now. I dealt with a frustrating acromioclavicular joint problem in the other shoulder for a good four months this past year. As a result, I spent an entire 12-week training cycle spinning my wheels and dealing with a lot of pain. Rather than have my distal clavicle cut off, I ultimately managed to figure out a way to correct the issue, and recently hit a 34-pound personal best bench press in competition.

Along the way, I've helped to fix a few hundred T-Nation shoulders and those of athletes and clients I see in person. It seems to have just become part of a normal day for me.

My intention here isn't to just blow some sunshine up my own butt, but rather to show you that I've got a pretty good perspective for what I'm going to write below.

Very simply, there are certain mistakes that many lifters with shoulder problems share in common. With that in mind, I decided to take a proactive approach and present to you my top sixteen recommendations for avoiding the problems in the first place. These aren't exhaustive, but I guarantee that if you take them to heart, you'll be much less likely to email me or, worse yet, give your orthopedic shoulder surgeon enough business to pay off his new Mercedes.

It seems logical, but we all know how tough it is to resist the exercises we've grown to love. Face the facts; you just might not be able to overhead press or bench with the straight bar.

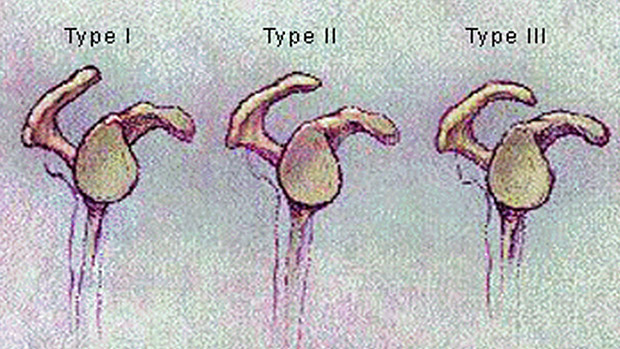

Not all bodies are created equal in the first place; a good example would be the different types of acromions, a portion of the scapula. Those with type III acromions are more likely to suffer from subacromial impingement due to the shape of this end of the scapula:

These are the 3 types:

- Type I Acromion: flat, minimal impingement risk, normal subacromial space

- Type II Acromion: curved, higher rate of impingement, slight decrease in subacromial space

- Type III Acromion: beaked, highest rate of impingement, marked decrease in subacromial space

Now, ask yourself this: when someone universally recommends overhead pressing, how often do you think they're consulting x-rays to determine if it might not be the best thing for you?

Moreover, not all bodies are equal down the road, either. If you're a type I or type II acromion process, you can "acquire" a type III morphology due to reactive changes. These changes may be related to a specific activity (e.g. weight-training) or just a case of chronically poor movement patterns (think of a hunchbacked desk jockey who's always reaching overhead).

There's almost always going to be something else you can do to achieve a comparable training effect without making things worse. So, the next time your shoulder starts to act up in the middle of a training session, put down the weights, take a deep breath, and walk over to the water fountain.

Use this stroll as an opportunity to recognize that something is out of whack and determine an appropriate course of action – including an alternative exercise. You might need to experiment a bit, but it'll come to you.

The serratus anterior is a small muscle, but it's of profound importance when it comes to scapulohumeral rhythm and, in turn, shoulder health.

Essentially, this muscle locks the scapula to the rib cage to prevent the scapula from winging out. It assists the pectoralis minor with protraction, but most importantly, it's involved in a delicately-balanced force coupled with the upper and lower trapezius for scapular upward rotation, a movement in which you need to be perfect to function safely with overhead movements.

Unfortunately, the serratus anterior will always be the first muscle to "shut down" in the face of any sort of scapulohumeral dysfunction, and activating it is a crucial component of all rehabilitation programs for the shoulder girdle.

I could literally give a day-long seminar on all the different pathologies in which serratus anterior dysfunction is involved in some way. So, why not take care of it ahead of time? Two great exercises are the scap push-up and supine 1-arm dumbbell protraction.

Scap Push-Ups

Supine 1-Arm Dumbbell Protraction

Stick with high reps on these; a few sets of 15-20 a few times per week will do wonders for you without interfering with the rest of your training.

This might very well be the most important one of all. I must admit that when I see a lifter benching with his elbows flared and his back flat, it makes me cringe – not only because he's ruining his shoulders, but also because he's really limiting his strength potential.

There's an old saying that a lot of great bench pressers have repeated when discussing the importance of the upper back in benching: "You can't shoot a cannon out of a canoe." If you don't have the underlying stability to press big weights, the soft tissues of the shoulder joint are going to suffer the consequences.

Stability is affected by both neuromuscular factors and positional factors; simply repositioning yourself on the bench can markedly increase your strength without any chronic changes to your neuromuscular system's ability to move the weight. Here's what you need to do:

- Line up on the bench so that your eyes are about 3-4 inches toward your feet from the bar (in other words, the bar is almost directly above the top of your head). From there, retract your shoulder blades hard. Next, push yourself back up until your eyes are directly under the bar; at this position, your scapulae should still be retracted, but also depressed down toward your feet as well. If you do it right, your rib cage should pop right up.

- Set your feet, and lock them into place. The position of the feet is going to be dependent on a number of factors, but what doesn't change is the fact that they need to be fixed in place.

- Decide on what degree of arch you want to use. For general health purposes, it doesn't need to be much. Obviously, powerlifters are going to need to push the envelope on this front. The more arch, the more it'll feel like a decline bench press. Declines will always be easier on the shoulder girdle than flat bench pressing.

- Grasp the bar and USE A HANDOFF from your training partner. Lifting off to yourself is a sure-fire way to lose the tightness you've just established in your upper back. Keep the shoulder blades back and down!

- As you lower the bar, keep the upper arms at a 45-degree angle to the torso; tuck the elbows instead of letting them flare out. It's well documented that the elbows-flared ("bodybuilder-style") bench markedly increases stress on the glenohumeral joint. Also, keep your wrists under your elbows instead of letting them roll back.

- Get a belly full of air and make the abdomen and chest rise up to meet the bar as it descends. Think of it as creating a springboard for moving big weights and, just as importantly, keeping those shoulder blades back to save your taters from undue stress.

- Do not excessively protract the shoulder blades at the top of the rep. You shouldn't lose your tightness prior to descending into the subsequent rep.

This is just the tip of the iceberg; definitely check out Bench Press 600 Pounds by Dave Tate and Yo; How Much Ya' Bench by Mike Robertson.

Now, check out these two videos of Carl LaRovera, one of my training partners at South Side. When Carl started with us, he was benching like a bodybuilder and – not surprisingly – had chronic shoulder problems. We fixed him up with six weeks of good structural balance in his training and, more importantly, some lessons on how to bench correctly. Here's was what he looked like on Day 1 of his South Side journey:

Bench Press - Elbows Flared

A few months later, he's pain-free and benching like this (although with more of an arch – plus a lot more weight – in actual training).

Bench Press - Elbows Tucked

Keep in mind that most ordinary weekend warriors and lifting enthusiasts don't have to push the arch; they just need to let the natural lumbar curve of the spine do its thing.

As Mike Robertson and I explained in detail in our "Neanderthal No More" series, poor posture is a big risk factor for hundreds of musculoskeletal injuries and conditions. Specific to the current discussion, rounded shoulders, an excessively kyphotic thoracic spine (think hunchback), and anteriorly-tilted, protracted scapulae will all predispose you to problems with the rotator cuff, long head of the biceps, labrum, and several crucial scapular stabilizers. With this in mind, I should introduce something I call the "23/1 Rule."

Very simply, this rule states that although you may do everything perfectly from a technique standpoint while you're in the gym for ONE hour per day, you have TWENTY-THREE hours to do everything incorrectly outside of the gym. This is especially applicable to the desks jockeys in the crowd who spend 8-10 hours per day at the computer in hopes of winning a Kyphotic Derby crown.

The solution is very simple: quit your job. Okay, I'm kidding. Instead, make a point of getting up and moving around as often as you can. Reach up to the sky, walk around, and do some doorway stretches for your pecs and lats (and your hip flexors, IT band, and calves, while you're at it). The best posture is the one that is constantly changing. Remember that although lifting is the straw that breaks the camel's back with respect to your shoulder problems, it isn't the only contributing factor; lifestyle plays a big role.

There's been a lot of talk of balancing horizontal pushing (e.g. bench pressing) with horizontal pulling (e.g. rowing), and vertical pushing (e.g. overhead pressing) with vertical pulling (e.g. chinning). For the most part, this system works pretty well.

Unfortunately, there are a lot of exceptions to these rules, and often times, people walk away more confused after hearing this than they were before the issue came up. With that in mind, I've come to the conclusion that about the only thing you can do is make a list of all the exercises that come to mind, and show how they "balance each other out."

I look for balance in three main pairs of antagonist movement patterns: scapular retraction vs. protraction, scapular depression vs. elevation, and humeral external rotation vs. internal rotation. In the balancing equation, absolute loading isn't nearly as important as total reps.

| Scapular Retraction | Scapular Protraction |

|---|---|

| All Rowing * | All Bench Pressing |

| Rear Delt Fly * * | All Flyes |

| Prone Trap Raise Variations * * * | Dips |

| Face Pulls |

* All Rowing — Excluding Upright Rows

* * Rear Delt Fly — Also involves horizontal abduction and external rotation

* * * Prone Trap Raise Variations — Counts as scapular depression, too

| Scapular Depression | Scapular Elevation |

|---|---|

| Scapular Wall Slides | Shrugs |

| Prone Trap Raise Variations | Upright Rows * |

| Behind-the-Neck Band Pulldowns | Cleans and Snatches |

| Prone Cobras to 10&2 (held for time) | Seated Dumbbell Cleans |

| Straight-Arm Lat Pulldowns (strict!) | Cuban Presses |

* Upright Rows — You'll find out how I really feel about upright rows in Part 2

| Humeral External Rotation | Humeral Internal Rotation |

|---|---|

| All External Rotation Variations | Bench Pressing, Pushups |

| Seated Dumbbell Cleans | Pullups/Pulldowns |

| Cuban Presses | Front Raises |

| Rear Delt Flyes | Dips |

| Prone Trap Raises | Overhead Pressing |

| Prone Cobras (held for time) | All Internal Rotation Variations |

Now, I've deliberately set these charts up so that you'll realize that the exercises in all left-hand columns are the ones most lifters tend to overlook altogether. If your posture isn't looking so hot, and your shoulders are bugging you, chances are that you need to shift to the left for a while until you've balanced out.

After reviewing the list of patterns above, hopefully you'll realize that adding in a full "shoulder day" to your programming is going to be overkill for this often-injured joint. You'll get virtually all the stimulus you need to build big shoulders from your bench presses, rows, chin-ups, and external rotation work. If you feel like you need to do direct traditional shoulder work, add in some overhead pressing and lateral raises sparingly – not on a day of their own.

While the shoulder joint is designed for mobility at the expense of stability, that's not to say that it isn't "exempt" from significant soft tissue restrictions. Getting some work done on these adhesions can make a huge difference in helping you to establish and maintain proper functioning in your shoulder girdle. Modalities such as Active Release, rolfing, Graston, massage, and even foam rolling can all make huge differences in breaking down all the junk you've amassed in your shoulder girdles.

For some reason, the seated cable row just doesn't get the love it deserves. This might be my single favorite movement for overall shoulder girdle health; you won't find a stricter means of training scapular retraction effectively with appreciable loading.

With bent-over, chest-supported, and one-arm dumbbell rows, the tendency is just too great to cheat, and there's always a tendency for the lats to take over for the scapular retractors. These benefits, of course, are dependent on proper execution of the movement; you can actually make your shoulder problems worse if you do any rowing variation incorrectly. The three most common cheating/substitution patterns we see are:

Hip Lumbar Extension

This is just your classic case of a guy who thinks he's on a rowing machine. Whether he's rounding his lumbar spine or not (he shouldn't) is of little concern to the shoulder discussion at hand; the hips and lumbar spine need to be locked into place. All the motion is at the scapulae and arms.

Scapular Elevation - Humeral Extension

The upper traps are dominant over the middle and lower traps and rhomboids as retractors of the scapulae, so the shoulder girdles elevate with retraction. Because the upper traps also anteriorly tilt the scapulae, the only way to get full range of motion on the movement is to extend the upper arms with the lats, teres major, and long head of the triceps. This pattern simply reinforces a kyphotic, forward head posture with internally rotated humeri.

Head Extension - Chin Protrusion - Elbow Flexion

For those with insufficient range of motion in both scapular retraction and humeral extension, the only way to falsely "get the feel" of full range-of-motion is to force the chin to protrude out – and then "finish" the movement with elbow flexion.

Essentially, it's a chin poke to bring the body further away from the pulley, and then a curl to bring the handle to the abdomen without actually extending the humeri or retracting the scapulae. It seems kind of silly to make more range-of-motion for yourself just so that you can do the movement incorrectly in that new range, huh? The video below features a spin-off version where the chin is just tucked to the chest, but the ending effect is the same; it just depends where the line of sight is.

Just to end on a positive note, here's a good seated-row:

That'll do it for Part 1; check back tomorrow for Part 2 and eight new secrets for healthy shoulders.