In the training world we often use analogies, simple sayings, or images to get our points across. Why? Because they make it easier for people to understand a more complicated concept.

"Stimulate, don't annihilate" was popularized by bodybuilder Lee Haney. It's a simple way to think about much more complex issues: hypertrophy, recovery, muscle protein synthesis, program design, etc. It's oversimplified, but we all remember it.

Of course, other simple phrases like "Eating fat makes you fat!" made a whole generation of dieters even fatter because they replaced all those evil avocados with processed carbs.

The human brain loves powerful, easy-to-grasp ideas. And since we love to argue in our field, we often resort to these simple sayings to "prove" our point. The problem is, many of these are misleading or even completely untrue. Here are three of them:

I admit that when I started out as a trainer I used that analogy too, even though I never fully bought into it. Now I know it's downright false.

First, all elite sprinters have over 90 percent fast-twitch muscle fibers, which indicate an ACTN3 RR profile. Without going too deep into genetics, ACTN3 is the gene that determines your muscle type as well as your muscle's response to training.

The ACTN3 profile, which is only found in about 10 percent of the population, has a very high ratio of fast twitch fibers. Remember, fast twitch fibers have a much greater growth potential, a greater mTOR response to training (which means more protein synthesis) and a faster rate of muscle damage repair, which will also lead to more growth.

Elite endurance athletes – those who are used in the comparison to elite sprinters – are very slow-twitch dominant. That's indicative of an ACTN3 XX profile, found in 10-15 percent of the population.

This is the "endurance" muscle profile: more slow twitch fibers (less growth potential), lower mTOR and greater AMPK (bad for muscle-building, good for endurance), a slower rate of muscle repair but a higher max VO2 and fat utilization capacity.

Simply put, those who reach a high level in sprinting have the genetics to be fast, powerful, strong, and muscular to begin with. Those who excel in endurance sports are the opposite.

Also, sprinters do a ton of heavy lifting. Heavy benches, squats, power cleans, deadlifts, etc. These guys put up pretty impressive numbers. Most elite sprinters squat in the 500 and bench press in the mid-300 pound range. Some of them squat in the 600's and bench in the 400's. Not world-class powerlifting numbers, but strong enough to have built a ton of muscle tissue along the way.

Have you ever seen an endurance athlete lift weights? Me neither! Well, in all seriousness, I have. And except for a few smart exceptions they all do BOSU ball exercises, curl-lunges combos, and quarter squats, all in the 15-25 rep range "to work on endurance." And they don't train hard or push themselves.

They don't have great muscle-building genetics to start with, and they don't do anything to stimulate muscle growth. Sprinters lift heavy; marathon runners don't. Is it that surprising that one is more muscular than the other?

And do you know what sprinters DON'T do? Intervals! Sprinters don't do intervals in their training, yet their bodies are used to "prove" that intervals are better at giving you a lean and muscular physique. See the problem there?

I've trained sprinters, I've trained with a track and field coach, I've collaborated with Charlie Francis (Ben Johnson's former coach), I train bobsled athletes (who train like sprinters) and I've never ever seen intervals being used.

A typical training session for a 100m sprinter will consist of 4-6 sprints (30-100m depending on the phase) with more than ample rest between sets – as long as 10 minutes between sprints. A good track coach would never have a sprinter do intervals. It would kill his CNS and destroy his sprinting mechanics.

Sprint training is all about quality. And to have the highest possible quality they avoid fatigue accumulation. You want to be as fresh as possible for each sprint. This is the opposite of intervals, where you want to build up a large amount of lactic acid and fatigue.

You know who does plenty of intervals? Endurance athletes! It's part of their weekly routine, and for many of them it's the primary training method.

So let me get this straight. I'm going to use a sprinter's physique to prove the superiority of intervals (even though they don't do any) over steady state cardio by comparing them to endurance athletes who actually do intervals. Isn't that messed up?

But Don't Freak Out...

I'm not saying that endurance training isn't without its problems. Endurance performance training will make it harder to build muscle – first by creating a large caloric deficit, then by inhibiting mTOR, and also by overproducing cortisol. But doing 30 minutes of steady state cardio 2-4 times a week isn't endurance training.

You can't look at an athlete who does hours of endurance work at a fast pace and believe that it's even remotely correlated to doing 30 minutes of slow cardio a few times a week. The two aren't even in the same ballpark.

Yes, excessive endurance training will jack up cortisol. But if you compare the cardio being done in gyms with intervals, the intervals will actually spike cortisol even more – cortisol release is relative to the amount of fuel being mobilized and adrenaline being released. Both are higher with interval work.

I'm not saying that intervals are crap or that steady-state cardio is king. Both can be useful if used properly and in the right dose. But the sprinter vs. marathon runner thing is simply dumb and intellectually dishonest.

This one is a little less dishonest. It's essentially true, but overrated. In reality, gaining a pound of muscle will increase daily energy expenditure by 15-25 calories, which is really not that much. It's equivalent to about one-third of an apple.

Arguably, if you gain 10 pounds of muscle it can lead to a greater caloric expenditure of around 200 calories per day. But it's still not anywhere close to what people would believe.

And honestly, most people do not add 10 pounds of muscle in a year of training once they're past the beginner stage. (They might gain 10 pounds of body weight, but not muscle.) The average male has the potential to add 30-40 pounds of muscle over his normal adult weight over his training career.

The point is that while adding muscle will increase energy expenditure, it's not as much as what people think and certainly doesn't justify eating like an ogre "because I have the muscle to burn it."

However, adding more muscle WILL make it easier to get leaner and harder to gain fat. But burning extra calories isn't the only (or even most important) reason.

It's also due to an increase in storage room. If you gain one pound of muscle you can store an extra 15-20g of glycogen in the muscles. So if you gain 5 pounds of muscle you'll be able to store 75-100g of glycogen more. This means you can eat more carbs before storing them as fat – the body will fill up glycogen stores before converting carbs to fat.

So, strictly from a mechanical standpoint, bigger muscles = more room for glycogen which means that I can have more carbs daily without storing them as fat.

Being able to consume more carbs daily will help you keep metabolic rate elevated because the conversion of T4 into T3 is dependent on carb intake and cortisol levels. Higher carbs normally means lower cortisol because the function of cortisol is to mobilize glycogen to elevate blood sugar levels. There's less need for that when eating carbs.

So, more muscle allows you to eat more carbs which helps keep your metabolic rate humming and also makes you more anabolic via a higher level of insulin and IGF-1.

Having more muscle also make the muscles more insulin sensitive. This is good for two reasons:

- If you're more insulin sensitive it means you need to produce less insulin to get the job done. If insulin is elevated less, it means that it gets back down quickly. As long as insulin is significantly elevated, fat mobilization is less efficient. So the quicker insulin comes down, the more time you'll be spending mobilizing fat for fuel.

- If your muscles are more insulin sensitive, you'll be better at storing nutrients in the muscle instead of as body fat. By the way, that's why Indigo-3G® is so effective: it specifically increases muscle insulin sensitivity.

So the car engine analogy isn't terrible, but there's a little more to it than most people know. And you actually don't "burn" that much more fuel when you build muscle. At least not compared to the calories you stuffed down your throat last weekend.

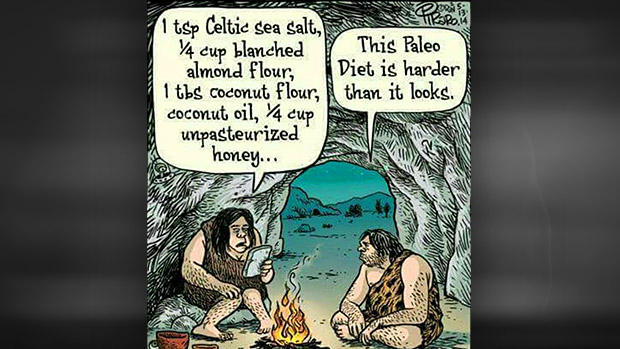

It's a powerful image, likely the best marketing hook we've ever seen in our field. And honestly, paleo is a pretty solid way of eating. You only eat unprocessed foods, but you also have plenty of variety and you don't cut out an entire macronutrient like keto or fat-free plans.

The thing is, it isn't really eating like a caveman. Are you eating organ meats, brains, and sucking bone marrow? Are you eating a lot of your food uncooked? Do you eat all of your food plain with no seasoning? Do you eat insects?

Do you only eat one meal, normally at night, maybe nibbling on some nuts or green veggies during the day? Do you sometimes go a few days eating nothing but veggies or roots and sometimes fasting completely?

Do you only drink water? Do you only eat foods that are without any pesticide, hormones, or other man-made substances? Do you eat with your hands?

No? Then you're not eating like a caveman. Nowadays you have paleo cookies, paleo cakes, and paleo salad dressings. I'm pretty darn sure that cavemen didn't bake cookies, not even paleo cookies.

The truth is, selling a diet as the "natural diet" just doesn't have the same ring to it as "the caveman/paleo diet." And chances are that it wouldn't have caught on nearly as much.

See, when it comes to dieting, the stronger the emotional buy-in you have, the easier it is to keep following it. You can have your paleo Facebook group (cavemen didn't have that either) to share stories, experiences, and recipes. It reinforces your belief and resolve. It's like a cult in many regards.

That doesn't mean it's not good, but you need to understand that the way you eat when you're "eating paleo" has very little to do with how cavemen really ate. And even amongst cavemen, there were many different diets depending on where they lived. The only constant that cavemen had was that they ate what they could find.

This is a case of telling a lie to get people to do the right thing. In this case, "doing the right thing" is eating a more natural diet and moving away from chemical-laden foods. That should be a powerful enough concept on its own, but not according to the normal human brain.

If believing that you're eating like a caveman reinforces your resolve to stick to a good healthy diet, all the best to you. But don't preach how this is "exactly" how cavemen ate and they were healthier and stronger than we are (there isn't really any data on that anyway). It has always been, and will remain, strictly a marketing ploy.

These are only three of the popular images or analogies used in our field. Sometimes they're downright false; other times they grossly oversimplify a concept. And in some cases, they're a lie that gets us to do the right thing or take a step in the right direction.

But keep in mind that clever phrases and analogies are there for one reason only: to get you to buy into a concept. Never lose your objectivity and your desire to research things further just because an image is powerful and "makes sense."