People need corrective exercise, that's no secret. According to the National Academy of Sports Medicine, corrective exercise entails movement assessment, inhibitory techniques, and muscle activation techniques that help to improve or "fix" musculoskeletal impairments, imbalances or post-rehabilitation concerns.

While I'll be the first to admit that corrective exercise is a crucial component of many of the programs I write for my clients, I'll also be the first to say that many of you (along with many fitness professionals) tend to go a little overboard, and fail to realize two important things.

- Getting someone strong(er) can actually be corrective in nature. You can always train around an injury.

- People waste too much time in the gym performing "cute" exercises. They still need a training effect when they're injured.

I interact with a lot of people who spend the majority of their day in front of the computer (aka: "computer guy"), and thus exhibit less than spectacular posture, and/or are suffering from any host of musculoskeletal dysfunctions. While it's great to use buzz terms like synergistic dominance or reciprocal inhibition, the truth is, I can fix many of their issues with a healthy dose of dynamic flexibility drills and soft tissue work using a foam roller or tennis ball.

The main goal of this article is to get you to realize that just because you're hurt, doesn't mean you can't train. On the contrary, getting stronger and creating a training effect will undoubtedly be corrective in nature. However that's not to say there aren't special circumstances where corrective exercise is of paramount importance. Of course all of this is highly individual. But I feel with proper programming and some thought, you can get all the corrective exercise you need without all the foo-foo nonsense.

The Law of Repetitive Motion, as popularized by Eric Cressey and Mike Robertson in their Building the Efficient Athlete DVD set, explains why getting your clients stronger can be corrective.

The law can be expressed in this neat little formula:

I=NF/AR

where:

- I = Injury

- N = Number of repetitions that exacerbate the problem

- F = Force of each repetition

- A = Amplitude (range of motion)

- R = Rest

In this case, "F" is expressed as a percentage of maximal strength: get tissue stronger, and each rep is perceived as less challenging overall. A great example would be someone with a history of chronic lower back pain. Get their glutes to start firing, and strengthen their posterior chain (among other things), and a lot of the "stress" or burden will be taken off of the lumbar spine.

Additionally, at Cressey Performance we go out of our way to explain to clients the difference between active and passive restraints. When referring to stress on our bodies, both active and passive restraints share the burden, and work together to keep the body functioning properly. Active restraints refer to muscle and tendon. Passive restraints entail bone, labrum, meniscus, and ligament.

As Eric has noted on several occasions, if the stress is shared between active and passive restraints, wouldn't it make sense that strong active restraints with good tissue quality and length would protect ligaments, menisci, and labra (and do so through a full ROM)? Hint: yes, it would.

While the phrase "just get strong" can mean different things to different people, it's important for trainees to realize that it's an integral aspect of program design that many fail to utilize.

It's fairly safe to assume that anyone who has been lifting weights for a significant amount of time has dealt with a nagging injury in his or her training past. Heck, I'm willing to bet a fair amount of you reading this article right now are dealing with some sort of nagging injury. Getting stronger is great, but if someone is dealing with a major dysfunction or injury, that can throw a monkey wrench in the works.

If you're like most people, you deal with an injury in one of the following three ways:

- Still train, but fail to make the proper modifications and end up only exacerbating the problem. We call this "being misguided."

- Still train, but you go way too easy on yourself. These are the people who do nothing but "functional" exercises for an hour, then hop on the elliptical to watch the nightly news. This is known as "being a baby."

- Stop training altogether, hoping that by doing so the pain will just go away. The clinical term for this method is "being a pussy."

The last thing someone wants is to feel like a patient when they train. Likewise, they also don't want to perform corrective exercises for half their session. People need a training effect. This is why it drives me crazy when I see trainees who have a history of knee pain (for example) spending 30 minutes trying to activate their gluteus medius.

Here's a better idea, lardbutt: how about losing those 20 pounds of excess blubber you're lugging around? Your knees will thank you.

Don't get me wrong, I'm all for corrective training modalities, and they definitely have their time and place. But as I stated before, a healthy dose of foam rolling and dynamic flexibility at the start of a session will shake loose most imbalances. This takes only five to ten minutes to complete.

Having said that, however, let's take a look at a specific example of a dysfunction or injury that most people encounter, and see how we can work around it, not only to fix it, but also to provide a training effect.

In her book Diagnosis and Treatment of Movement Impairment Syndromes, Shirley Sahrmann describes the pinching of any structure between the head of the humerus and the acromion as impingement of the shoulder. This may include the bursa, the rotator cuff tendons (most commonly, the supraspinatus), or the tendon of the long head of the biceps muscle.

Furthermore, "sharp or pinching pain is usually present around the anterior, lateral, or posterior aspect of the acromial process of the scapula during shoulder abduction or flexion. Often the pain will be referred to the area of the insertion of the deltoid muscle." In other words, you have an ouchie.

How can we fix this while at the same time create a training effect? Also, is it possible to maintain current strength levels, or even work on getting stronger during this time?

I know this is going to sound like heresy to many guys reading this, but it's probably best to lay off benching for a few weeks. "Lay off benching for a few weeks" doesn't translate to, "Okay, I'll just stop benching three times per week, and do it twice per week instead." I literally mean stop benching for a few weeks. Trust me, it won't bring about the end of the world.

However, because I know guys are still going to bench no matter what I say, I'll offer some simple suggestions and modifications.

Learn to bench the right way, for crying out loud. When I ask most trainees to show me how they bench, it generally looks like this:

As you can see from the video, the back is flat, elbows are flared out, and somewhere I'm looking on with what I like to call my bitter bench face.

Making some minor adjustments will go a long way as far as protecting that shoulder.

As you can see in this video, I have a slightly arched back, my shoulder blades are pinched together, and my elbows stay tucked close to my body. I'm more stable, and my shoulder won't hate me as much, because there's not as much stress placed on it. It may feel weird in the beginning, but your shoulder will thank you in the long run.

Come to think of it, who says you have to do a full range bench press? Try utilizing movements such as board presses and floor presses, along with dumbbell variations. Doing so will undoubtedly maintain your strength levels while staying in a pain-free range of motion.

Row, Row, and Row Some More

More specifically, more horizontal rowing in the form of seated cable rows, standing cable rows, chest supported rows, etc. For most trainees a ratio of 2:1 or 3:1 (pull:push) will help tremendously in regards to correcting any imbalances. In other words, for every one "pushing" exercise, you will perform two to three "pulling" exercises. So even if you're not benching as much as you're used to, you can still maintain quite a bit of upper body strength during this time. I'll even go so far as to say that improving your upper back strength will translate to a bigger bench press, and an improved posture to boot.

More Push-Ups

Unlike the bench press (an open chain movement), push-ups are considered a closed chain movement (hands do not move), and as a result allow a little more wiggle room for the scapulae to actually move around a bit. And while most will proclaim push-ups to be too easy, I'm willing to bet that many of you reading this can't even do ten in the first place, let alone with proper form.

That being said, you can always make push-ups more challenging by performing blast strap push-ups, band-resisted push-ups, push-ups vs. chains or with additional weight on your back (x-vest, weight plates).

Conversely if regular push-ups hurt, you can modify them by elevating yourself on a power rack to a position where they don't hurt or you can utilize isometric training.

70% of your total muscle mass is below the belt (my girlfriend knows what I'm talkin' about. Yeah, baby, yeah!). Just because your shoulder hurts, doesn't mean you can't train your legs. This calls for lots of single leg variations, which are generally absent from most programs anyway.

In addition, we'll probably have to make some modifications towards squatting. Absent are the back squats, and in their place we can use giant cambered bar or safety squat variations. For those that don't have access to specialty bars, front squats would also be a viable alternative.

In their DVD "Secrets of the Shoulder," both Gray Cook and Brett Jones note that deadlift variations can actually help strengthenthe rotator cuff through a mechanism called irradiation. The stronger you squeeze a bar (or dumbbell or anything where your grip comes into play), the stronger all the nerves fire along that chain, forcing the rotator cuff muscles to fire and to "pack" the shoulder joint.

Both Cook and Jones note that just because we test rotator cuff strength with external and internal rotation, doesn't mean we should train them in that fashion as well.

We want to get the rotator cuff to do what it's designed to do at the subconscious level, and utilizing deadlift variations will do just that. By signaling the scapular retractors to lock weight in (through our grip), we are then able to transfer force from our lower body through the "core" into our upper body through a stable shoulder. The key here is to tell yourself to crush the bar or dumbbell. You'll notice that your rotator cuff will fire automatically, and the shoulder will "pack" itself back into proper position.

Fillers are low level, flexibility/activation/self-myofascial release drills that I like to utilize between sets. Your gym time is valuable, and spending half of it trying to "activate" stuff is just a waste. Likewise, spending upwards of five minutes in between sets watching highlights on ESPN or discussing what happened on last night's episode of Lost is a time killer.

By implementing fillers into your programming you'll get much of your corrective exercise done while you're training. As a result, you'll make better use of your down time and actually do something productive, rather than flirt with that hot little personal trainer, who, just between the two of us, you have no chance in hell with.

Keeping with the above shoulder impingement example, there are a few goals I like to achieve with the fillers I use.

Improve Thoracic Spine Mobility

As Cook and Jones note in their DVD, you can't have scapular stability if you lack thoracic spine mobility. With limited t-spine mobility, the scapular stabilizers (in this case the serratus anterior) don't have a good attachment point and can't orient themselves to their anchor (the rib cage) to function normally. By implementing some simple mobility drills for this area, one will definitely see an improvement in scapular function, and thus a decrease in discomfort.

Improve Hip Mobility

Research indicates there may be a relationship between shoulder dysfunction and a hip ROM/strength deficit on the opposite side. Force is often transferred in diagonal patterns (also called the Serape effect), and can help explain why a problem in the right shoulder might be linked to a dysfunction in the left hip, and vice versa.

Improving one's hip mobility can oftentimes alleviate many issues, not only in the shoulder, but throughout the entire body as well.

Loosen up downward rotators, and strengthen serratus anterior and lower trap

We tend to be very "upper trap" dominant from all the benching, shrugging, and over-head pressing in our programming. Throw in atrocious form on things such as seated rows and chin-ups (trainees tend to shrug the weight), as well as faulty breathing patterns, and you have the perfect recipe for what's known as scapular downward rotation syndrome. In a nutshell, we need to loosen up the downward rotators (pectoralis minor, levator scapulae, and rhomboids), and strengthen the upward rotators (specifically the serratus anterior and lower traps).

This is especially true for those who sit at work all day in front of a computer or for those who live relatively sedentary lifestyles. And yes, even if you do go to the gym 3 or 4 times per week, if you make a living sitting on your ass, you're still what I would consider sedentary. Throwing in some extra stretching between sets for the hip flexors, hip rotators, lats, and pecs will go a long way in helping you feel better.

Improve breathing patterns. This ties in very well with thoracic mobility, and is something I touched on briefly in my Limiting Factors article. Ask someone to take a deep breath, and you're likely to see their shoulders (and traps) rise. Most people only use the upper third of their lungs when breathing, and as a result fail to utilize their diaphragm.

As a result many people have overactive traps, which only exacerbates their shoulder pain. By correcting our breathing pattern, and learning to utilize the diaphragm (also called crocodile breathing), we now get expansion of the rib cage, which automatically maintains mobility of the thoracic spine.

Lets take a look at what a program should look like for someone who has shoulder impingement. Keep in mind that this is only an example.

Day #1

| Exercise | Sets | Reps | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Deadlift Variation (Trap Bar, Conventional, Sumo, Rack Pull) | 5 | 5 |

| A2 | Extra T-Spine Extension on Foam Roller | ||

| B1 | Band Resisted Push-Ups | 3 | 8 |

| B2 | Seated Cable row, Neutral Grip | 3 | 6 |

| Filler | |||

| Squat-to-Stand/Seated 90-90 (15 sec per side) | 6 | 5 | |

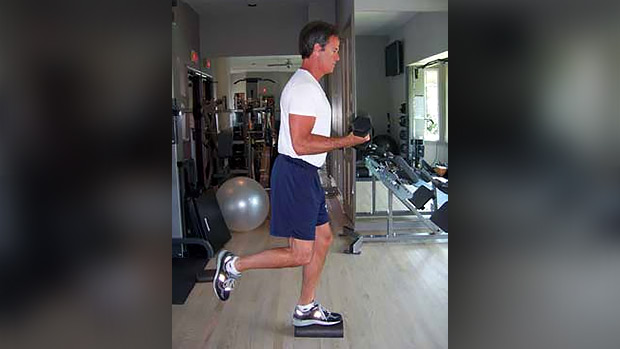

| C1 | Dumbbell Step-Ups | 3 | 8/leg |

| C2 | Face Pulls With External Rotation | 3 | 12 |

| Filler | |||

| Cross-Body lat Mobilization | 3 | 8/side | |

| D | Single Leg Prone Planks | 3 | 20 sec/side |

Day #2

| Exercise | Sets | Reps | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Dumbbell Floor Press | 4 | 6 |

| A2 | Chest Supported Row | 4 | 10 |

| Filler | |||

| Warrior Lunge | 4 | 5/side | |

| B1 | Glute Ham Raise | 3 | 8-10 |

| B2 | Chin-Ups | 3 | 5 |

| Filler | |||

| Scapular Push-Ups/Kneeling Hip Flexor Stretch | 12 | 20 sec/side | |

| C1 | One-Legged Romanian Deadlift | 3 | 10/leg |

| C2 | Prone Trap Raise | 3 | 12 |

| D | Pallof Press | 3 | 10/side |

Day #3

| Exercise | Sets | Reps | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Squat Variation (Front, Giant Cambered Bar, Safety Squat Bar) | 6 | 4 |

| A2 | Crocodile Breathing | 6 | 1 min. |

| B1 | 2-3 Board Press | 3 | 5 |

| B2 | Dumbbell Reverse Lunge | 3 | 8/side |

| Filler | |||

| Behind-the-Neck Pull Aparts/Levator Stretch | 10 | 15 sec/side | |

| C1 | Standing Cable Row | 4 | 8 |

| C2 | EZ Bar Triceps Extensions | 4 | 10 |

| Filler | |||

| Quadruped Extension-Rotation | 3 | 20 sec/side | |

| D | Reverse Crunches | 3 | 12 |

Note: I would also try to get in at least two days of energy system work on your "off" days consisting of 15-20 minutes of intervals followed by 10-15 minutes of steady state work. Also, don't eat like a nimrod.

Hopefully I was able to shed some light on a rather murky topic. Again, I'm not saying that corrective exercise is useless or unimportant. On the contrary, I think it's an integral component of any good program. I just feel that for most trainees, (read: not all) it should be incorporated into a program not bea program. Additionally, just because you're hurt doesn't mean you can't train. Contrary to what many people believe, creating a training effect around an injury isn't that hard. It just takes a little thought and imagination.