Here's what you need to know...

- From prolonged planks to thousands of sit-ups, ab training has gotten wacky and dysfunctional.

- The core musculature has the ability to create tension for extended periods of time, but that doesn't mean you need to train it with endurance work.

- Test for core weakness, then adopt the exercises shown below to build a strong, truly functional core.

Does being able to hold a plank for 45 minutes mean you have a strong core? How about doing 100 reps of ab crunches using the traditional (butchered) form?

These incomprehensible metrics have pushed their way into our fitness norms and they can be blamed for their fair share of spinal pain and dysfunction.

In a misguided gym culture, "more" always constitutes better. More time added to passive planking, more reps added to ab crunching, more, more, more!

While more can be a good thing in training, like adding some plates to your PRs, more for the core is usually a misguided goal.

It's time for a reality check. Let's take a step back and not only assess what you're doing, but also why you're doing it. Let's get rid of the time-wasters and the potential injury inducers.

Let's ask the tough questions, like, what are the chances that the muscles you're supposedly targeting aren't even being trained?

Some old-school practices refuse to die even after we've figured out that they're ineffective. People are still confused about abdominal strength, aesthetics, and transferable function to performance.

Busting these myths is the first step toward rectifying effective and efficient ab training.

1. Do 1000 Sit-Ups A Day... or More!

Back in the 80's, people couldn't get enough of the Herschel Walker bodyweight training program.

As the story goes, young Herschel would knock out anywhere from 2000-5000 sit-ups a day, building an Adonis-like body that produced one of the most impressive athletic physiques around. (And he still looks great today!)

But if anecdotes and folklore alone lead to game-changing aesthetics gains, well, every McDonald's addict in America should be able to develop a set of abs that turns heads at the beach.

The type of volume Herschel put through his core on a daily basis was pretty insane. Like most gifted athletes, he rose to the top despite his training methods, not because of them.

For the rest of us, this type of ab training only causes sore lower backs, crappy posture, and surgical-level abdominal soreness that just doesn't translate into strong, visually appealing abs.

2. Hold Your Planks, Like, Forever!

In 2014, Mao Weidong set the world record for the longest plank hold according to the Guinness Book of World Records. Four hours and 26 minutes!

Yes, this happened in China, and yes, the man who set this record is a physical anomaly that both movement scientists and psychologists will never fully understand.

Any good coach, trainer, or practitioner in the fitness industry that was asked about this heroic physical feat responded in the same way: "That's the stupidest thing I've ever seen." Harsh! But there's a good reason for this.

While this feat was described as an impressive showing of "core strength," was it really?

I'm going to go out on a limb and say that Mao's abdominal wall was not maximally contracted the entire duration of the hold. However, he was able to hold on just long enough to position himself in a perfect orientation to hang out on the anterior pelvic ligaments and tendons of the hip.

World class strength? Not so much. Precursor to tendinopathies and ligamentous trauma? Yeah, that's more like it.

3. The Core Needs Endurance Work

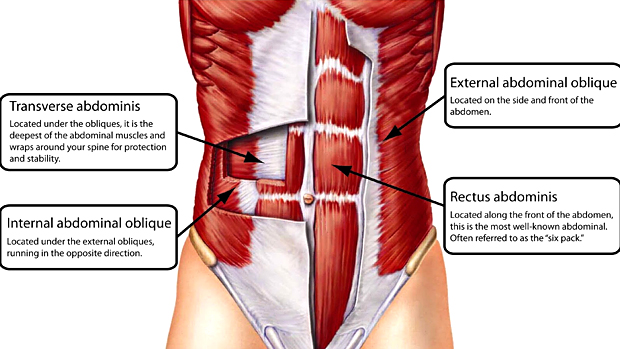

The core, made up of the four separate but synergistically moving layers of the abdominal wall, has been misunderstood in both anatomy and function.

One of the most misguided myths of core training is the idea that the core must function with ultra-endurance capabilities in order to be considered functional for an athlete.

The core has the physiologic capabilities to create tension throughout its musculature for extended periods of time. However, if your primary purpose is to transfer function into performance, then the core acts more as a phasic set of muscles with the acute ability to generate force and tension quickly for short periods.

This unique action of the core working synergistically together is what allows us, as humans, to be mobile, powerful, and dynamically impressive without losing spinal stability with every quick, twitchy move we make in the gym and on the field.

With this known, training the rectus abdominis (the "six-pack" muscle) or either of the obliques to function as tonic muscles not only is impeding potential functional gains, but also wasting time that would be better invested in transferable strength and stability.

The abdominal wall is comprised of four layers of musculature, all with distinct fiber orientations, actions and functional capabilities.

But, when working in conjunction with one another, the core can also act as a functional unit to connect segments of the body together while creating a stable environment for serious force to be produced out of the legs and arms.

The deepest layer of the core is the transversus abdominis. This muscle's fibers run horizontal in orientation while also acting largely as a tonic stabilizer of the abdominal cavity. It's attachment directly to the spine also makes it important for lumbar and lower thoracic spine stabilization.

The internal and external obliques are located on both sides of the anterior-lateral thoracic cage and act to side-bend, rotate, and aid in flexion of the spine. The internal oblique on the left side works in unison with the external oblique on the opposite side, and vice versa, to coordinate smooth, stable movements of the core.

Finally, the celebrity six-pack core muscle is the rectus abdominis. This muscle is the most superficial muscle in the group and runs from the bottom portion of the sternum to the pubic bone of the pelvis. It's the primary flexor of the lumbar spine.

Since a majority of core training is centered on the rectus, it's important to figure out whether your hard-earned sweat dollars are going towards developing both strength and hypertrophy in this muscle, or is it just a big waste of time that could lead to potential chronic lower back pain and hip flexor dysfunction.

The training goal for doing a sit-up or any other spinal flexion movement is to target the rectus abdominis. Many obsessive-compulsive ab trainees have no idea if this muscle is even being targeted through their training.

All they know for a fact is that their spines are moving into flexion, which has generally been accepted to be a bad thing biomechanically when programed too frequently with far too high of training volumes.

Due to the compensation patterns developed, secondary to overtraining the rectus abdominis, the level of muscle recruitment can actually be less over time, while developing movement dysfunctions from secondary muscles that are supposed to be aiding in spinal flexion taking over the exercise altogether.

It's imperative that we get back to the basics of training – figuring out how to maximally target a muscle through movement.

Resetting your core and starting over from scratch can be a powerful thing, especially if the self-tests below show weakness in a muscle that's been your primary focus six times a week for over a decade!

Standard manual muscle testing (MMT) for the rectus abdominis is simple, and that's exactly what we need after the overly complex ab routines that have been dominating training sessions these days.

First, lay down on your back with your knees absolutely straight. From this position, place both hands on the back of your head without yanking through the neck with your arms.

This arm position is used not to play a role in neck trauma, but rather to extend your center of mass out further away from your core, creating a longer and heavier leaver arm to control once the movement starts.

From the hands behind the head position, tuck your chin to the chest, bring your head, shoulders and arms off the floor, and sit-up only using your rectus abdominis.

No cheating on this. If you see momentum being used from your hip flexors, legs or shoulders, repeat the test. The only one you're cheating is yourself!

The goal for this test is to be able to clear your shoulder blades off the floor only using the strength of your rectus abdominis. This is considered a normal finding indicative of a normal functioning rectus in terms of strength capability.

If you aren't able to achieve this position without cheating, we'll simplify down the test by placing your hands across your chest like you're hugging yourself, and complete the same movement only using your rectus.

If your shoulder blades are able to get off the floor in this position, you're still in the clear for having a strong-ish core, but may need some remediation.

Finally, if you find yourself unable to get your shoulder blades off the ground with arms to your chest, simplify your arm position one more time and place your arms extended and in front of your hips.

This again shifts the center of mass towards the core, making the resistance of the movement less. The goal is the same – get your shoulder blades off the floor without cheating. Even if you pass this modified test with the arms out straight, you have some work to do to fire up that core.

If you find yourself unable to get the shoulder blades off even in this position, you are officially graded as having poor or non-existent rectus abdominis strength. You'll need to focus on activating and strengthening this muscle pronto.

For those who were able to execute either the hands behind the head or hands across the chest testing movement, you're in the clear... for now.

Remember, your rectus abdominis is a muscle and should be trained as such. Things like rep/set schemes, training volumes, and frequencies should by no means be tossed out the window and replaced with 8-minute abs.

Execution, activation, and progressive overload is the key to training, so keep that in mind.

If this simple test humbled you, don't sweat it. Here's how to remediate your rectus abdominis activation, strengthen your spinal flexors, and do so in an intelligently-designed program that won't leave you bent over in pain after every hard "core" training session.

Follow the program below with pristine form and focus and you'll be well on your way to a strong, functional core. Use this tri-set as either a pre-training activation drill or a post-training finisher to emphasize core function and strength.

A1. Supine Core Isometric Hold 4 sets of 8 second hold

Tuck your chin, flex your abs, all while staying flat on your back.

A2. Supine Rectus Abdominis Sit-Up with Position Assistance 4 sets of 8 reps, 30 seconds rest

Place a pad under shoulder blades for slight flexed starting position. Hold maximal tension in rectus for half a second before lowering under control.

A3. RKC Plank 4 sets of 5 second holds, 15 seconds rest

Generate full body tension maximally for prescribed time.