The Question

What training method or diet strategy did you once think was good, but now you don't anymore?

I changed a lot of my views over the years, but the biggest change is related to carb intake.

When I first started out in the strength coaching field I was a diehard low-carb guy. I believed that most people needed to limit carbs if they wanted to get really lean, and that you could build a significant amount of muscle mass on a low carb diet.

Here are some of the reasons behind those beliefs:

- I was never a lean guy growing up. I wasn't really "fat" but I didn't have abs or muscle definition either. It's only when I lowered my carbs, using Bodyopus by Dan Duchaine, that I was able to get lean for the first time. So right off the bat my mind started to believe that low carb was the only way to get ripped for people who aren't naturally lean.

- One of my biggest influences early on was Charles Poliquin. One of the key things he taught at the time was low-carb eating. His famous phrase was, "You have to earn your carbs; you must be at 10% body fat or less to consume a higher amount of carbs."

- When I first dieted down using a low-carb diet I already had a good amount of muscle mass. I was squatting (high bar) 600 pounds, front squatting 475, benching 405, snatching 315, and push pressing 315 for 5 reps. I was 228 and 5'9". But I didn't look impressive because I was carrying a decent amount of fat. When I got down to under 10% body fat I looked a lot more muscular. But I actually didn't carry more muscle than before. In my mind it was possible to gain muscle on a low-carb diet, because it looked like I had added muscle.

- The only time I looked good was when I ate a low-carb diet. So I thought that I needed to eat that way to look lean and muscular. But when I wasn't trying to get shredded I'd eat a crappy diet: pastries, hamburgers and fries, kid cereal, candy, etc. And I blamed carbs for gaining fat. So in my mind low carb eating = lean and muscular, moderate or high carb eating = strong, but fat. But I was likely eating over 5000 calories during my high carb (but low quality) diet versus 2500 when I was low-carbing it.

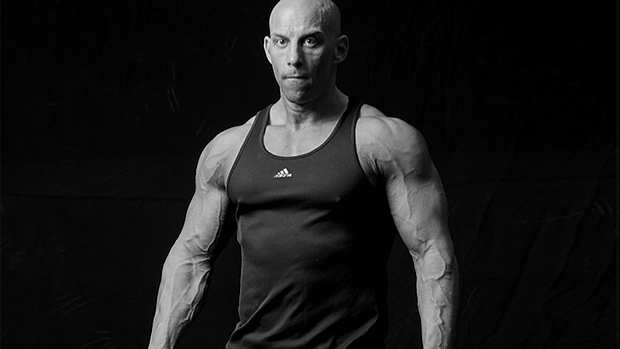

I had a change of heart a few years back when I achieved my biggest muscular bodyweight (228 pounds at under 10% body fat) eating lots of carbs. That was in 2013 when I was in Colorado, training at Biotest HQ.

At the time we'd just come out with Plazma™, Mag-10® and Finibars and I was getting over 300 grams of carbs from those alone, and my supper was normally four turkey burgers (only the bun and the meat). All and all I was likely having 400-500 grams of carbs per day. And this is when I gained the most muscle past the beginner stage.

I started to read more about carbs and muscle gain and I realized that hormonally speaking, eating a low-carb diet makes it really hard for most people to put on a significant amount of muscle mass. Low carb lowers IGF-1 (the most anabolic hormone in the body), increases cortisol levels (cortisol's main function is to increase blood sugar levels when they get too low, which will happen during a low-carb diet) and decreases insulin (which is also anabolic even though it can be anabolic to fat cells too).

Even today when I want to gain muscle I make sure that carbs are high. At the moment I'm eating to get stronger and bigger and consuming over 400 grams of carbs per day. I'm up to 231 pounds and still have abdominal definition.

When I did my last photoshoot and got into my leanest condition to date I never went below 100 grams of carbs on my low-carb days (consumed pre, during and after the workout) and up to 300 grams on my higher days, and got leaner than I did during my low-carb days.

In fact, more and more studies are coming out showing that if protein and calories are the same, it doesn't matter for fat loss if the non-protein calories come from fat or carbs.

Yes, some people will feel better on a lower-carb diet while others will be the opposite. But I no longer believe that low-carb dieting is the best way to eat to optimize your physique. Christian Thibaudeau

The "need" for a training log.

Ask any little old Italian grandma for her sauce recipe and, after she laughs and hits you with the rolling pin, she might say, "A lotta tomato, some basil, some garlic, and a little bit of grandpa's wine." While you're pretty sure she deliberately left out a few ingredients, you might've also been expecting a slightly more useful and specific answer.

Maybe you hoped her instructions would sound like it was straight out of a cookbook: "Four cups of diced tomato, one tablespoon dried basil, four garlic cloves, three ounces of wine." But that's not how grandmas cook. They work by feel, not by the book. Sometimes, you need to train like grandma.

I used to be pretty convinced that a training log was essential for results. Without being able to flip back a few pages and see what you've done, how do you truly know you've gotten stronger? And by exactly how much? And how quickly or slowly?

Keeping a log is absolutely beneficial. It helps beginners aim for basic progressive overload with concrete "more reps or more weight" targets for each workout. Logs can also help advanced lifters re-trace specific steps like exercises, volume, and frequency that lead to big PRs (or big injuries).

However, I'm now understanding that a training log isn't mandatory. There's a lot to be said for simply showing up at the gym and playing the workout by feel, not worrying about recording every movement with plans to refer back, analyze, and treat like a puzzle piece within some grand scheme. The biggest benefit is that it forces you to really tune-in to your body and its capabilities for the given day.

If 225 is moving slowly, something's off and you shouldn't jump to 275 just because it's what you hit for 6 reps last week. Not having a log to refer to forces you to autoregulate and work within an "every day max," not some pre-determined weight the book says you're supposed to use.

If you're training for size, lifting by intuition is almost-definitely how the best-built bodies have trained forever. Some light warm-up sets and then adjust every set depending on how good the burn was. Simple, effective, time-tested, no notebook required.

Spend a few weeks, maybe even a couple of months, ditching the training log and treating each workout as a standalone session. Each set and each individual rep becomes that much more important. String enough of those kinds of sessions together and you'll end up improving the quality of every workout in the future. Chris Colucci

I believed in intermittent fasting, gave it a fair shot, then changed my mind on it.

Intermittent fasting (IF) first came on my radar almost a decade ago from several big names in the fitness and nutrition industry. Proponents talked about all the benefits which went beyond fat loss, like reduced blood lipids and blood pressure, reduced markers of inflammation, increased cellular turnover and repair, increased growth hormone and metabolic rate, etc.

So of course this piqued my interest not only for me but also my clients. And we all spent time trying variations of IF, including the common 16-hour fast with an 8-hour window of eating. We also did 24-hour fasts and 12-hour fasts.

I wanted to believe in this strategy, and for some it's still valid. But after giving it a fair shot, I found some fundamental issues with its effectiveness and practicality. Hunger suppression was one area that made me change my mind on IF.

A number of hormones that regulate hunger, appetite, and satisfaction are in play after a meal. For example, both leptin and insulin decrease hunger, giving your brain the message of satisfaction and "turning off" the need to eat.

A side effect of fasting is that, for some, these hormones get out of balance, leading you to become unresponsive to cues that tell you whether you're full and should stop eating. And if people alter their hunger hormones, they find themselves battling an uncontrollable appetite. Once they eat, the satiation cues telling them to stop won't register. Their appetites are insatiable. I know a number of people who have done IF and found that they've binged following fasting.

Another negative is the excess stress and insomnia from fasting. Any time you go without food for long periods you activate the flight or fight sympathetic nervous system and increase cortisol secretion in order for the body to mobilize energy stores.

For people who already have a lot of stress in their daily life (including training) fasting may increase it further, upping the body's cortisol levels, which has a number of negative effects. Cortisol is catabolic – it can break down muscle tissue and make it harder to build muscle. The combination of fasting and cortisol can produce obsessive thoughts about food which raises anxiety, causing a further release of cortisol.

High cortisol and the activation of the hypocretin neurons incite wakefulness, leading to insomnia. I experienced this and heard from others who did too.

Finally, a study by Bogdan looking at the effect of Ramadam fasting found significant alterations in testosterone release, suggesting an alteration in circadian function.

A lot of IF advocates will promote studies that show no drop in strength or lean mass from their fasting protocols. One 8-week study with natural bodybuilders did show that the test group and control group achieved similar results in strength and muscle mass. However, a big point is that testosterone and IGF-1 did decrease significantly in the fasting group.

I also struggled to be proactive both physically and mentally during specific points in the day when fasting. But this isn't uncommon; even IF advocates schedule meetings and other appointments during the feeding window.

Although there's evidence to support this protocol as a fat loss strategy, for me there are too many factors that make IF unsuitable because of how it affects stress, sleep, and testosterone production – all vital components in building muscle. Also, the inability to control your appetite and nutritional choices during the feeding windows can produce more problems than benefits. Michael Warren

Frequent max effort training.

The Maximal Effort Method was a popular strategy among those who trained at Westside Barbell. And it works. It does make you stronger, both physically and mentally. I know this from having used the method for a long time in my own training and training athletes. Here's an example of max effort work from my strength-focused days:

So why would I change my mind on it? I realized that there's only so much energy you have in a day, a week, and a life. When you get older and have to handle more stressors – beside the stress of training – you'll realize that max effort work is taxing. Done too frequently at this stage, it can really mess you up (injuries, fatigue).

But this doesn't just apply to lifting as much as possible; all max efforts are taxing. Sprinting, jumping, and going "all out" on any activity too frequently is a bigger investment than most adults can make.

Max Effort work is a display of strength more than it actually trains strength, and frequent use of the method can cause systemic fatigue. If you live and die by your ability to display high performance, you have to choose your training methods wisely.

I've come to the conclusion that frequent max effort training DRAINS you more than it TRAINS you. Intermediate to advanced athletes should use it sparingly. Beginners can use it more frequently because they're way below their strength potential.

When you've reached a good level of strength (for your sport), save your max effort to when in really counts – competition. Then, unleash what you've been wanting to display! Your competition will see the difference. Eirik Sandvik

I changed my beliefs on foam rolling.

When I first started to learn the Olympic lifts, my lack of flexibility became clear. My training partners were advancing faster than I was because I couldn't squat below parallel, let alone attempt an overhead squat needed for the snatch.

I got frustrated with my inflexibility and turned to Coach Internet for help. The most popular method was foam rolling and self-massage techniques for loosening up muscles. There were also banded techniques with the intent of mobilizing joints to create range of motion.

My sessions were starting to turn into some kind of kinky self-beating in the hope that I'd get a better squat. It seemed to be working; the depth of my squat was increasing and I was able to do an overhead squat. But I was always sore and always having to roll just to keep up my flexibility.

I started studying massage, making my techniques better. By replicating proper physiotherapist techniques, I was able to make any ache or pain disappear in a matter of minutes! It was roughly around this point that I started coaching and I started sharing my techniques with others. They thought it was awesome. Quick fixes, instant mobility.

So why did I change my mind on it? Knowing what I know now, self-massage is grossly misinterpreted. It's a small addition that may, possibly, help your recovery from something like a really intense leg session.

Pain is a signal that's trying to tell you something. Using equally painful self-massage techniques to override that pain is basically telling your body to shut up. Sure, my range of motion improved, but there was no stability with it whatsoever: my hips were loose and weak, and my shoulders were horribly unstable. My body was creating reoccurring tightness to try and help keep my joints safe. So what did I do? Loosen them up again and keep going! And by doing so, I picked up a string of injuries including a serious back injury.

Now it's the main thing I help people with: teaching them how to move better all of the time. If you want to increase your range of motion, using movement progressions that make you take your joints through a full range of motion should be your main priority.

Stability and mobility have to be earned; cheating it will only end in injury. If you have spare time and want to massage yourself, that's cool, but you have to ask yourself, "What does my body learn from this, and how does it make me stronger?" Tom Morrison

I changed my mind on carb intake.

I used to love low-carb dieting for fat loss. It worked for me and many clients. The first time I got shredded I followed a low-carb approach. This created an emotional attachment with the nutritional strategy. In my mind, if you did anything else you were a fool.

Fast forward a few years and I rarely have my carbs lower than 300 grams per day and I'm as lean, if not leaner, than I ever was with the low-carb approach. The same goes for many of my clients.

The simple reason why I thought low-carb eating was valid is that it worked. For that same reason, I still think it has validity, but it's not optimal, especially if you're a guy who carries a lot of muscle mass or aspires to build even more muscle.

Going low carb allowed me to create and maintain a calorie deficit. This is the single most important element to a successful fat loss phase. Back then I thought there was something magical going on with insulin. This was when paleo was in its heyday. But nope. Nothing was magical. I was just eating less than I burned.

Once I took a more logical approach to fat loss and applied a hierarchy of needs, everything got easier. I was in a position where I could eat a greater variety of foods and still get shredded. That made the whole process more sustainable. A plan is only as good as your ability to adhere to it!

So what are the hierarchy of needs when it comes to nutrition? I call it "The Three T's":

- Total Calories

- Type of Calories (i.e., ratio of macronutrients)

- Timing of Calories

Then to get shredded and maintain muscle I began asking myself the following questions: What's the best style of training during a cut? And what nutrition best supports this training?

The answer to the first question is, the most volume you can recover from. The answer to the second has a few more points to consider:

- A calorie deficit

- Enough protein to maintain muscle mass

- Sufficient fat to support optimal hormonal function

- Carb intake as high as possible while still losing fat

Why are carbs so important? Carbs are the preferred energy source of high intensity activity (lifting weights). They're the most anabolic macro, as long as your basic protein and fat needs are met. So, carbs have an important role to play in preserving muscle while dieting. They fuel hard training and help you recover from hard training. Better training with better recovery makes for better progress and bigger muscles. For that reason, I now emphasize their importance when helping anyone looking to get lean and keep muscle.

This isn't to say low-carb dieting doesn't have a place. It's just that you need to pick the right tool for the right job. To be the leanest, most muscular version of yourself, very little of your time should be spent going low carb. Tom MacCormick

I was once a proponent of ass-to-grass (ATG) squats, but now I recommend squatting to parallel.

When I became a strength coach 15 years ago, I was convinced that ass-to-grass was the optimal squatting method. After all, ATG squats produced a greater stretch in the legs, induced greater levels of muscle soreness, and was exponentially more challenging than squatting to parallel or above.

In addition, all the hardcore lifters seemed to say anything short of ATG was heresy. So of course they had to be correct, right? Not exactly. After several years of witnessing a number of musculoskeletal and orthopedic issues gradually develop in mine and my clients' bodies, I began to examine what other coaches began advocating. The trend was shifting to a more personalized approach – finding a squat depth for each individual's ability and anthropometrics.

Many of us abandoned the one-squat-fits-all approach, and we advised the clients that could squat ATG in a pain-free fashion to do so, while we advised others to squat to parallel or slightly below depending on their individual needs. So each lifter would squat to their deepest pain-free range of motion.

Sounds reasonable, doesn't it? But there's more to the story. When I first began implementing this approach I thought for sure this was the key for optimizing the squat pattern. But after several more years of analyzing my clients, I began to notice a surprising trend.

Those who could only squat to approximately 90-degrees or parallel made the largest strength and size gains in their lower body AND they experienced the least amount of joint and soft tissue inflammation. In fact, the parallel squatters rarely needed to foam roll or perform extensive warm-ups before their squats.

In addition, those who squatted with 90-degree positions actually improved their movement mechanics including their gait, running, jumping, and agility. More surprising was their mobility and flexibility actually improved.

In contrast, the lifters who were able to squat ATG with no apparent issues actually had to perform lengthy warm-up sessions, soft tissue work, mobility drills, and stretches to combat the host of issues produced from their squats.

And unfortunately, the ATG squatters actually experienced a number of unusual gait and movement aberrations, not to mention actual decrements in their mobility and stability most likely due to the accompanying inflammation. They also seemed to hit consistent plateaus in various markers of athletic performance.

Furthermore, my collegiate and professional athletes who switched to parallel squats began noticing greater improvements in explosive power in their jumping and sprinting activities with markedly reduced joint pain and inflammation.

Fortunately at this time I began my PhD in kinesiology which allowed me to dive deeper into optimal squat mechanics. After examining various elements of muscle physiology, biomechanics, and neurophysiology, it became apparent that 90 degree angles and parallel joint segments were ideal not only for squats but for nearly all movements.

This notion held true for any human being regardless of their individual differences in anthropometrics. After spending well over a decade coaching hundreds of athletes of all different shapes, heights, ages, and sizes, the one thing I can tell you is that while maximal range of motion and mobility boundaries vary greatly from person to person, proper squat depth, mechanics, and ideal range of motion are very similar from individual to individual. (More info: The Real Science of Squat Depth.)

Individual differences in anthropometrics indicates maximal range of motion, not optimal range of motion. Joel Seedman, PhD

I changed my mind on dietary fat.

I used to try to eat less than 20 grams of fat a day, but I've changed my mind on the amount and the type. Why? Because extremely low-fat diets can hinder hormone production along with joint and heart health.

Equally important is the source you consume. Polyunsaturated fats tend to be unstable and quick to oxidize. Oxidation leads to inflammation in the body which is at the root of a number of diseases. It's particularly harmful to joints and heart health.

I now diet on 80-plus grams of fat from sprouted almonds, green olives, avocado oil, Flameout® and grass-fed, organic beef. Off-season I'll consume even more. Consuming fat in a calorie deficit seems to aid the efficiency in which my body burns fat.

Fat burning efficiency is important if your goal is to get ultra-lean. Dropping down my fat consumption in the final weeks of a diet causes my body to readily shift to burning its own fat stores, leading to favorable, stage-ready body composition. Mark Dugdale