Does Supercompensation Work?

A lot of the information you read about peaking for a competition revolves around "supercompensation." You dramatically increase training volume and intensity for 7-14 days then, one week out from the competition, you bring training stress way down and increase carbs to supercompensate. This leads to an increase in performance.

Sounds sciency and smart. But does it really work?

Well, it depends. If you're an endurance athlete, it might. It seems to work pretty well for swimmers. But if you're a strength athlete, it won't do anything. It'll give the illusion of working, but it really doesn't.

Here's Why

First, when we talk about supercompensation we're really talking about increasing glycogen storage in the muscles. The theory? By dramatically increasing training volume and reducing carb intake, the body will upregulate the enzymes responsible for storing glucose.

When you flood your body with tons of carbs and reduce volume for 3-7 days before an event, the body will store more glycogen than it normally would if you had not done things to "deplete" it.

In theory, by storing more glycogen (supercompensation) you have more fuel available for your event and you'll perform better. This can work if your sport is dependent on the amount of stored glycogen you have.

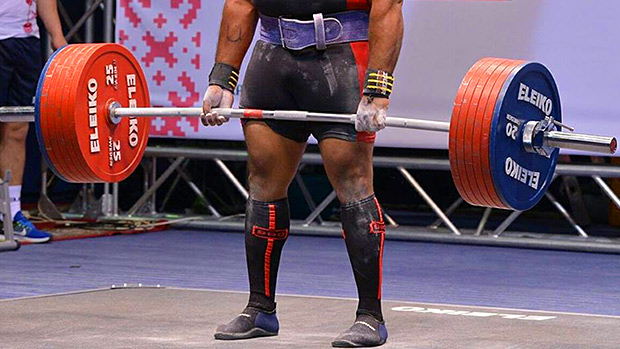

Endurance sports might benefit from higher glycogen storages, and glycolytic sports certainly would. But strength sports like powerlifting and weightlifting are not at all dependant on glycogen stores for performance since the main fuel in these sports is ATP-CP.

While glycogen supercompensation might help the bench press and possibly the squat by providing an increase in passive joint stability – as noted in Question of Strength 58 – it's certainly not the main driver of performance.

Does That Mean You Shouldn't Deload?

No, you should. But you must understand what the deload will do so you can plan it properly. It also means you shouldn't do a stress week or two (7-14 days) prior to the deload to create a supercompensation effect.

You can't supercompensate the nervous system. You can't supercompensate the endocrine or your muscle mass. Just because you're trashing those systems by training too much for a short period of time, it doesn't mean that these will rebound even higher. The nervous and endocrine systems don't function like your glycogen storage.

Here's what happens during a deload and why it can give the illusion of supercompensation of neurological resources.

First, You Need to Understand Two Things

1. The connection between cortisol and adrenaline

Cortisol increases the conversion of noradrenaline into adrenaline. The more cortisol you produce, the more adrenaline will increase.

Four main training variables can lead to an increase in cortisol (thus adrenaline) during training. Those are...

- Volume: The more energy you need, the more cortisol you release.

- Intensiveness: The closer to the limit you're pushing your sets, the more cortisol you produce.

- Psychological stress: Mostly related to the amount you're lifting.

- Neurological demands: Learning new exercises, using more complex movements, or doing a complicated workout structure.

2. Beta-adrenergic downregulation

When you overstimulate the beta-adrenergic receptors, they downregulate. In layman's terms, this means when you're producing a boatload of adrenaline that connects to the beta-adrenergic receptors, these receptors can downregulate. As a result, you respond less and less to adrenaline.

Since adrenaline increases strength, speed of contraction, and motivation (among other things), if you respond less to it, strength and power will go down. On the other hand, the more sensitive your receptors are, the more strongly you respond to adrenaline and the more force your muscles will be able to produce.

Now Let's Connect the Dots

If you dramatically increase training intensity and volume (stress week), you produce more cortisol. This leads to a very high level of adrenaline. This high level of adrenaline can downregulate the beta-adrenergic receptors, decreasing strength potential.

After that stress week, you feel like crap and your performance drops. Then you deload, reduce volume, intensity, and maybe even frequency. You drop assistance exercises, which decreases neurological demands too.

This all leads to a decrease in cortisol levels, and in return, a much lower level of adrenaline. The beta-adrenergic receptors now become much less stimulated and they recover their original reactivity. Now you respond to your adrenaline again. You regain your strength and motivation. You think, "My deload worked, I supercompensated!"

No, you didn't. You just recovered the responsiveness to adrenaline that you lost by doing too much!

A study by Fry et al. (2006) found a 37% downregulation of the beta-adrenergic receptors after only two weeks of very high intensity/high frequency work. By doing one or two weeks of high demand work prior to a competition, this downregulation will cause a significant drop in performance (5-10%).

But why would you cause this downregulation on purpose, only to have it brought back up to the normal level during your deload? There are no benefits and you actually risk not being able to fully recover the receptors' responsiveness completely. You also risk getting injured during this phase of high volume/high intensity.

On top of that, there's a good chance that even prior to the stress week(s) you already have some downregulation going on. And the stress of the upcoming meet will also increase cortisol (psychological stress) which will further jack up adrenaline – leading to more desensitization.

My recommendation is to deload so that you'll get the beta-adrenergic receptors as responsive as possible, but do not precede that with a period of dramatically increased training stress.

Here's How That Would Look

Just do your regular program and one week out deload like this:

Assuming this is a Saturday meet, drop all assistance work one week out.

- Saturday (seven days out): Work up to your opener on squat and bench press. Do three singles at 90% of your opener on the deadlift.

- Sunday (six days out): OFF

- Monday (five days out): Squat 3 x 2 using 90% of opener, bench 3 x 2 using 90% of opener, deadlift 3 x 1 using 80% of opener.

- Tuesday (four days out): OFF

- Wednesday (three days out): Squat 3 x 2 using 80% of opener, bench 3 x 2 using 80% of opener.

- Thursday (two days out): OFF

- Friday (one day out): Activation – squat 3 x 1 using 70% of opener, bench 3 x 1 using 70% of opener.

- Saturday: Meet

For the deload, we have:

- Extremely low volume

- • Zero complexity (minimalist workouts)

- • Low intensiveness (everything leaves 3-4 reps in the tank)

- • Low psychological stress

- • Low neurological demands

You'll minimize cortisol response as much as possible, lowering adrenaline and increasing beta-adrenergic receptor reactivity.

Nutrition and Supplementation Strategies

Here are some strategies you can use to maximize the reactivity of those receptors:

Training Days

- Rhodiola: Take two capsules (200 mg) in the morning. As an adaptogen, it makes the body better at responding to stress. It does this in part by balancing dopamine, serotonin, and adrenaline.

- Power Drive®: Take one serving in the morning. It'll keep your nervous system optimized. Often during a deload, dopamine decreases and the nervous system, even if it's rested, is more sluggish. This may cause performance to drop. Power Drive will help a lot.

- Plazma™: Take one serving pre-workout. There's no need for more than that because the volume is so low. You're using it mostly to lower cortisol production. Pre and intra-workout carbs lower cortisol production during the workout.

- Magnesium (or ZMA®): Use it post-workout and in the evening. Magnesium will decrease the binding of adrenaline to the beta-adrenergic receptors. This calms you down but also makes it easier for the receptors to re-sensitize. The less adrenaline binding there is, the quicker the upregulation will occur. Try 500 mg of magnesium; it's enough for that purpose although you can go as high as 1000 mg in the evening.

- Glycine: Use it post-workout and in the evening. Glycine inhibits (calms down) the nervous system decreasing cortisol and adrenaline. As an amino acid it also increases mTOR activation post-workout, which can increase protein synthesis and muscle repair. Take three to five grams post-workout and in the evening.

Off Days

Only take the Rhodiola, Power Drive®, and magnesium or ZMA® in the evening.

Note: Creatine could help you, mostly by increasing cell volumization, which can help with passive joint stability, making you stronger. If you're already taking it, continue right through the meet. If you're not taking it, but have in the past, and didn't have any adverse reaction, add 10 grams per day for the pre-meet week.

If you've tried it and had gastrointestinal issues, don't take it. If you're going to be very tight on the weigh-in, you might want to skip it since it might increase your body weight by two pounds.

As for your food intake, it really depends on where you are relative to your weigh-in. Ideally you'd keep carbs high during the week both to help decrease cortisol levels and to keep glycogen stores full. Fuller glycogen stores will help create passive stability, especially at the shoulder joint and should help you bench and squat heavier.