Here's what you need to know...

- Free weights and machines both have their advantages and disadvantages.

- Free weights excel by forcing you to use your stabilizer muscles and control the load. They fall short keeping consistent tension throughout the range of motion.

- Food quantity and quality matter, but focus on quality and you'll take in fewer calories without even counting them.

- Men and women exhibit wide ranges of responses to resistance training. In one study, upper arm strength gains ranged from 0% to over 250%. Genetics matter.

- Your particular genetics may respond better to a different program. Or maybe you're just not working hard enough.

- Daily intensity and volume (set/rep) variations are more effective than weekly volume variations for increases in maximal strength.

Four False Dichotomies of Fitness

A false dichotomy is a logical fallacy where only two choices are presented when, in fact, other possible choices exist.

These dilemmas reflect oversimplified thinking and are usually characterized by black and white, "this vs. that" type language. Let's take a look at four common workout and diet dichotomies.

1 – Machines vs. Free Weights

The whole idea of pitting free weights against machines is like pitting fruits against vegetables. Both training modalities offer a unique benefit the other misses, so it makes sense to do them both in order to makes your workouts more comprehensive, just like eating both fruits and vegetables will makes your diet more nourishing.

Free weights excel by forcing you to use your stabilizer muscles, allowing you to move naturally and requiring you to control not just the load being moved, but also the path of the movement.

Free weights fall short when it comes to keeping consistent tension on the working muscles throughout the range of motion. And that's the area machines excel in better than free weight applications.

In other words, there's one disadvantage all free weight and cable exercises have that a machine doesn't – gravity!

Example: During any style of biceps curl, the point at which your biceps is being maximally loaded (stimulated) is the point in the ROM in which your forearm is at a 90-degree angle with the load vector. If you're using free weights, gravity is your load vector. So, the point of maximal loading would be when your elbow reaches 90 degrees of flexion or when your forearm is parallel to the floor.

If you're doing biceps curls using a cable machine, however, the cable itself is the load vector. The point of maximal loading to your biceps is when your forearm makes a 90-degree angle with the cable.

Here's the kicker: The farther away you move from a 90-degree angle with the load vector, the shorter the lever arm becomes and the less work your biceps have to do. That's why, in a free weight biceps curl, the closer you move toward the bottom or top of the range, the less work your biceps get because the lever arm is shortening.

That's precisely why people tend to rest between reps at the top and bottom position when doing barbell or dumbbell curls. This applies to any free weight exercise in that they're all being loaded by a single load vector (gravity or a cable).

On the other hand, machines are designed with a CAM system, which isn't dependent on a single load vector like free weights or cables. Instead, the CAM is set up to offer you a much more consistent resistance throughout the entire range of motion.

This also gives you much more time under tension because your working muscles don't get the same chance to rest at the bottom or top position of the range like they do when using free weights.

While you can absolutely build plenty of muscle size exclusively using free weights, there's no reason to avoid machines. For strength and muscle, machines can and should be used in conjunction with free-weights.

2 – Fat Loss and Calories: Quantity vs. Quality

Any time someone says that the relationship of how many calories you consume per day to the number you burn per day is the single most important factor when it comes to determining whether you lose fat, someone else always tries to refute it by bringing up the fact that the quality of the calories you eat matters. They present it as an "either/or" proposition.

Listen, research looking into the potential advantages to diets emphasizing protein, fat, or carbohydrates has found that reduced-calorie diets result in clinically meaningful fat loss regardless of which macronutrients they emphasize, and it doesn't discount that some calories are more nutrient dense than others. After all, we've all heard the term "empty calories." It's simply to demonstrate that one can still be well nourished and overfed.

So, both food quality and quantity are important factors that should be considered together, because, as important as it is to eat high quality, nutrient-dense foods for general health, you can still gain fat from eating "healthy" if you eat too many calories relative to what you're burning.

That said, my general recommendation is to start by focusing on the quality of the foods you eat – emphasizing fruits, vegetables, high-quality proteins (meats, eggs, fish, etc.) and whole grains while limiting refined foods, simple sugars, hydrogenated oils, and alcohol. You'll likely end up taking in fewer calories without even actually counting them.

3 – Genetics vs. Hard Work

The big problem with statements like "hard work beats talent" is that it always assumes that "hard work" is the answer.

However, the undeniable reality is that while hard training makes a difference for everyone – put more in, get more out – some people benefit more from the same type and amount of hard training than others.

In other words, some people are more trainable than others based on their genetic make-up when it comes to seeing results from the same given training program. Some people put work in and get little out of it, while others put the same amount of work in and get (much) more out of it.

The scientific evidence in this area demonstrates that a wide variability in individual, genetically-influenced training response occurs in both aerobic training and strength training.

In regards to different genetic responses to aerobic training, one study subjected 99 two-generation families to stationary bicycle training programs to increase aerobic fitness. All the families received the same training program consisting of three workouts per week of increasing intensity for 20-weeks. DNA was taken from all 481 participants.

The results revealed marked inter-individual differences, such as: the range in VO2 max improvement spanned from 0% to 100%, depending on the family heritage. About 15% of participants showed little to no improvement, while another 15% increased their VO2max by 50% or more.

Additionally, it should be noted that person-to-person variability in aerobic training responses has been observed not only in the Heritage Family Studies, but also in other studies and populations.

In regards to different genetic responses to strength training, two studies showed that individual differences in gene and satellite cell activity are critical to differentiating how people respond to weight training.

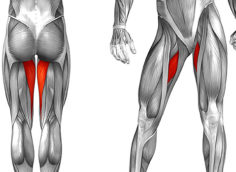

The 2007 study put 66 people of varying ages on a four-month lower-body strength training plan consisting of three exercises: squats, leg presses, and leg extensions. Each person was matched for level of effort as a percentage of their 1RM. A typical set was performed for 11 reps at 75% of 1RM.

At the end of the training period the subjects fell into three groups: those whose thigh muscle fibers grew 50% in size, those whose fibers grew 25%, and those who had no increase in muscle size at all.

Despite identical training, subjects had a range of 0% to 50% improvement. As David Epstein, author of The Sports Gene: Inside the Science of Extraordinary Athletic Performance said:

"...differences and trainability were immense. Seventeen weightlifters were extreme responders who added muscle furiously; 32 were moderate responders who had decent gains; and 17 were non-responders whose muscle fibers did not grow. It seems that some people's bodies are better primed to profit from weightlifting as the subjects who made up the extreme muscle growth group had the most satellite cells in the quadriceps, waiting to be activated and build the muscle."

In addition, other studies have validated these results finding that men and women exhibit wide ranges of responses to resistance training, with some subjects showing little to no gain and others showing profound changes. One in particular involved 585 subjects. In 12 weeks of study, upper arm strength gains ranged from zero to over 250%!

You could certainly say that the harder someone trains the more likely one is to get a positive response. I certainly wouldn't argue with that. But we can't ignore the fact that some people are low responders to certain exercise programs while others are high responders. So, if you're a low responder it's likely that you'll get fewer results than your peers who are following the same program.

The Reality: Both hard work and genetics matter, and both greatly influence your training results. So, both must be considered when finding a training direction and revaluating your current results.

When an individual may not seem to be responding much to a given training program, sure, it's a possibility they're simply not working hard enough or being dedicated enough.

However, it's also a possibility the individual is putting in the dedication and work, but just not responding well because the program doesn't fit well with their genetic profile.

Just because they're not responding well to a program doesn't mean they won't respond to a different training program. So, it's smartest to experiment with different types of training programs to look for something to which they have a better genetic response.

The take away point is this: As important as it is to encourage everyone to train hard, it's also dangerous not to also inform everyone that hard work isn't everything – it's your individual response to it.

4 – Hypertrophy: High Volume vs. High Load

As stated in Brad Schoenfeld's seminal research paper, the three primary mechanisms for increasing muscle hypertrophy are muscle tension, metabolic stress, and muscle damage.

That said, both lifting heavy loads for lower volumes and lifting lighter loads for higher volumes can bring about muscle tension, and therefore create a stimulus for muscle growth.

Not to mention, muscle damage doesn't just occur mechanically from heavy loads lengthening the muscle fibers eccentrically, causing the actin and myosin to be forcibly ripped apart. It can also be caused chemically. During repetitive effort exercise such as high-rep sets when you're using more oxygen, reactive oxygen species (ROS) or free radicals form. These ROS can cause muscle damage.

Additionally, a 2002 study compared linear periodization (LP) and daily undulating periodization (DUP) for strength gains. The training involved 3 sets – bench press and leg press – 3 days per week.

The LP group performed sets of 8 reps during weeks 1-4, 6 reps during weeks 4-8, and 4 reps during weeks 9-12. The DUP group altered training on a daily basis (Monday, 8 reps; Wednesday, 6 reps; Friday, 4 reps).

The researchers concluded that making program alterations on a daily basis was more effective in eliciting strength gains than doing so every 4 weeks.

More recent studies have not only also found that daily intensity and volume (set/rep) variations were more effective than weekly volume variations for increases in maximal strength, but using daily undulating periodization also may lead to greater gains in muscle thickness (size).

What the scientific evidence tells us is, the debate between high load vs. high volume lifting is another debate we shouldn't be having, as incorporating both heavy load / low volume training along with lighter load / higher volume work in an undulating fashion, seems to be the smartest approach.

References

- An P, Pérusse L, et al. Familial aggregation of exercise heart rate and blood pressure in response to 20 weeks of endurance training: the HERITAGE family study. Int J Sports Med. 2003 Jan;24(1):57-62.

- Hautala AJ, Mäkikallio TH, et al. Cardiovascular autonomic function correlates with the response to aerobic training in healthy sedentary subjects. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003 Oct;285(4):H1747-52.

- Kohrt WM1, Malley MT, et al. Effects of gender, age, and fitness level on response of VO2max to training in 60-71 yr olds. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1991 Nov;71(5):2004-11.

- Bamman MM, Petrella JK, et al. Cluster analysis tests the importance of myogenic gene expression during myofiber hypertrophy in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2007 Jun;102(6):2232-9. Epub 2007 Mar 29.

- Petrella JK1, Kim JS, et al. Potent myofiber hypertrophy during resistance training in humans is associated with satellite cell-mediated myonuclear addition: a cluster analysis. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2008 Jun;104(6):1736-42.

- Hubal MJ, Gordish-Dressman H, et al. Variability in muscle size and strength gain after unilateral resistance training. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005 Jun;37(6):964-72.

- Schoenfeld BJ. The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training. J Strength Cond Res. 2010 Oct;24(10):2857-72.

- Schoenfeld, Brad J.; Contreras, Bret. Postexercise Muscle Soreness a Valid Indicator of Muscular Adaptations? Strength & Conditioning Journal: October 2013 - Volume 35 - Issue 5 - p 16-21.

- Rhea MR, Ball SD, et al. A comparison of linear and daily undulating periodized programs with equated volume and intensity for strength. J Strength Cond Res. 2002 May;16(2):250-5.

- Prestes J, Frollini AB, et al. Comparison between linear and daily undulating periodized resistance training to increase strength. J Strength Cond Res. 2009 Dec;23(9):2437-42.

- Miranda F, Simão R, et al. Effects of linear vs. daily undulatory periodized resistance training on maximal and submaximal strength gains. J Strength Cond Res. 2011 Jul;25(7):1824-30.

- Simão R, Spineti J, et al. Comparison between nonlinear and linear periodized resistance training: hypertrophic and strength effects. J Strength Cond Res. 2012 May;26(5):1389-95.