Coachademics

It's become a trend for trainers (even good ones) to overcomplicate things. Not sure what I'm talking about? Here's an example. Try to guess what this exercise is using the following clues:

- It incorporates the lateral fascial line with the arm fascial line.

- It involves the lateral oblique subsystem.

- Due to the positioning of the load, along with the movement pattern involved, the core musculature is forced to activate to create spinal stability through stiffness.

- The shoulder is given a small distraction force, which the CNS has to offset by creating joint centration and compression for enhanced shoulder stability.

Know what the exercise is? It's a single-arm biceps curl. As you can see, its benefits can be described in ways that elude the person needing to do them.

I call it "coachademics." Yep, I had to coin a term for it because it's THAT common. A coachademic trainer will try to sound academic by using overly-complex explanations when a far simpler explanation or description would get the point across faster. By overcomplicating it, they make basic concepts sound like rocket science.

It's almost as if people want to "rebrand" basic exercises by adding unnecessary complexity to make it sound like certain exercises or applications offer more than they actually do.

For example, I've heard trainers talk about "grooving the movement pattern" when they're taking about learning the exercise technique... or simply, practicing. I mean, you've got to virtually dislocate your shoulder reaching for that one.

Once you start seeing it you can't stop. And you too will notice the extra big words and jargon some trainers come up with to make what they do sound more impressive.

Is it a problem, or should we just shrug it off? Well, it adds unnecessary confusion and can over exaggerate the importance of certain things relative to other, well-established exercises and techniques. To clear the air, here are the practical translations of common, overly-technical sounding terms trainers use.

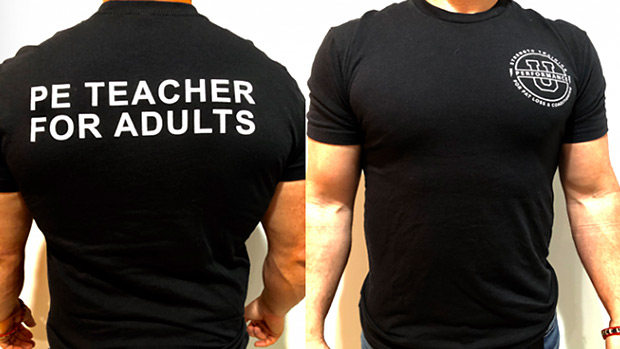

Translation: Personal trainer

It's amusing how many trainers try to give themselves flashy titles that they print on the back of their work shirts, or put in their bios when we're really just glorified P.E. teachers. This is why it says "PE Teacher for Adults" on the back of my company shirts.

More importantly, good frames can't save bad paintings. There's no fancy title in the world that can cover up for not being great at your craft. And people can see right through that stuff anyway. If you're great at what you do, people will see that as well because talent draws attention.

Translation: Warm-up

A (dynamic) warm-up is a transition stage from normal activity to more athletic activity. A cooldown is just the opposite – a transition stage from athletic activity to more normal activity.

There are general and specific warm-ups. Specific warm-ups serve essentially as "build-up" sets because they're simply lighter, less intense versions of whatever exercises you're getting ready to do. You're building up gradually to your working intensity.

For example, if you're going to run sprints, you first do some light runs, building up your speed with each round. If you're going to do a heavy lift, you first do a few lighter sets to build up to your working weight.

The warm-ups many trainers provide in articles and books are usually general warm-ups because they involve a few general athletic movements and coordination exercises. They get your heart rate up and also prepare your entire body for the more athletic workouts that follow. These warm-up sequences also often include exercises that help you maintain and increase your overall range of motion.

Translation: Cardio or conditioning

What we're really talking about here is improving your ability to resist fatigue and recover between bouts of physical activity.

Conditioning, sometimes called work capacity, really comes down to power-endurance. As the name implies, power-endurance training will make you better able to produce the same level of power for a longer time – the length of competition.

In other words, many of the low-rep, high-load training methods help you peak your power in short bursts, but they don't require you to call upon every ounce of strength and power you have, even when you're tired.

Conditioning protocols require you to expend a high amount of effort for extended periods of time, and with minimal recovery, which is exactly what power endurance is.

Keep in mind, Power = Strength x Speed. Everything we do in life, in or out of the gym, involves an expression of power. Whoever finishes the marathon first produces the most power. Whoever does the most push-ups in a minute produces more power than those who do fewer.

If it used to take you a minute to get up a flight of stairs, and now it takes only half a minute, then you're producing more power than you used to.

Chances are, you don't think of any of those things as "power" activities. There's no explosive component like you'd see in a sprint or a one-rep-max bench press. But there's still a foundation of power there.

When coming up with conditioning workouts, you don't have to understand the energy systems of the body. You just have to apply the principle of specificity. Look at the work-to-rest ratio demands of the sport or activity you're training for, and use those same or similar timeframes in your training. Then look at the style and pace involved in your target activity and make sure you use the same or similar style and pace during your conditioning methods.

Translation: Isometrics

Many trainers recommend anti-spinal exercises to train the abs, and they avoid spinal flexion exercises (like leg raises or crunches) because they feel it's more functional for sports. They often call anti-spinal movement exercises like planks "stability exercises," but they're really just isometric exercises.

Perhaps their emphasis on isometrics is what made them fancy-up the name. Everyone already knew what planks and isometrics were, so they added words to their sacred cow in hopes that it would sound more important.

The funny thing is, trainers and coaches don't call isometric biceps curls "elbow stability training," nor do they call isometric squats "knee stability training."

That logical inconsistency aside, there are limitations of isometric training for performance because the strength gains it produces are extremely joint-specific and they transfer to those specific positions better. This is why I don't ride the no-spinal movement core exercise bandwagon, which is a topic I covered in great detail in Dynamic Training for Abs & Obliques and other T Nation articles.

Translation: Functional transfer

First off, the word "functional" is used here, not as a buzzword but in a manner consistent with its accepted, dictionary definition. Functional applies to something that has a special task or purpose. So functional transfer involves applying the principle of specificity to select exercises that can help you improve in specific athletic tasks.

For example, squats can transfer into improved vertical jump height. So, this is simply about applying the principle of specificity, which has been defined as follows in the National Strength and Conditioning Association's Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning (2000, 25-55):

"The concept of specificity, widely recognized in the field of resistance training, holds that training is most effective when resistance exercises are similar to the sport activity in which improvement is sought (the target activity). Although all athletes should use well-rounded, whole-body exercise routines, supplementary exercises specific to the sport can provide a training advantage.

"The simplest and most straightforward way to implement the principle of specificity is to select exercises similar to the target activity with regard to the joints about which movement occur and the direction of the movements. In addition, joint ranges of motion in the training should be at least as great as those in the target activity." (1)

Some exercises provide obvious and direct transfer to improved performance in sporting actions, whereas others provide less obvious transfer – indirect transfer. Since some exercises don't necessarily reflect the specific actions of many common movements in athletics, their positive transfer into improved performance potential is less obvious.

This fact has led some trainers to label them as "nonfunctional" and therefore not valuable. And we know that's false. This fact doesn't make an exercise bad, and it certainly doesn't make it nonfunctional. It simply means that the less specific an exercise is, the more general it is.

General exercises offer general transfer into improvements in human performance by increasing muscle hypertrophy, motor-unit recruitment, bone density, and connective tissue strength, which can improve overall health and reduce injury risk. Therefore, these two categories of exercise, specific and general, offer different benefits.

Each type benefits certain interdependent components of fitness and performance that the other category may miss.

Translation: Listening to your body

Don't go as hard on your workouts on the days you don't feel as good. Get after it on the days you feel like running through walls. If an exercise hurts, don't do it and find a different exercise that doesn't.

Pay attention to how you feel instead of overriding your body's feelings just to get through a prescribed workout. In other words, use common sense.

Translation: A training plan or a training direction

Periodization is NOT what exercise programming is or is not about. Periodization represents training methods of exercise application, organization, and prioritization you can use in the programming process.

That said, I define exercise programming (or program design) as

the organization and prioritization of exercises to create a stimulus that elicits certain adaptions (the training goals).

You see, resistance exercises are simply ways to put force across tissues. And the sets, reps, tempo, etc. used are exposures. More volume (sets and reps) mean more exposures. So, the exercises are a training stimulus, and the adaptations (results) you get come from type (load, speed) and amount (sets and reps) of exposure you had to it.

Translation: Training weeks, training phases, and training blocks

Training weeks are made up of a group of training days. Training phases are made up of a group of training weeks based upon a given training theme (strength, power, hypertrophy, etc.). And training blocks are made up of several phases of training leading up to a specific date or event.

For example, a 12-week offseason training program for American football leads up to their preseason program (preseason training block).

Translation: Load phase and volume phase

Since you focus on adding volume in the accumulation phase, and focus on adding load in the intensification phase, it's easier to call them the "volume" and "load" phases because that's really what they are.

Translation: Lift heavy, lift fast, lift for higher reps

Thinking about these concepts in more practical terms, instead of just as concepts used by some powerlifters who follow a certain training method, helps us to see them in a broader context of applications outside of the powerlifting world.

You don't often (if ever) see field, court, or combat sport athletes doing speed rows using bands, but it's commonplace to see athletes and lifters of all stripes doing bench press with bands because they're copying what they see powerlifters do.

These athletes want to improve their power (strength x speed) but aren't training to be powerlifters. So there's no reason they should be treating their bench press differently than other exercises like rows since they're training to improve their overall physical ability, not just their ability to perform three lifts.

Things become a lot clearer, and our ability to design becomes more effective, when we do less exercise memorizing based on a certain school of thought, and do more exercise analyzing based on universal training principles.

What determines a good program is how well it sticks to the four foundational principles of training: individuality, progressive overload, specificity, and variety. It's the training principles that determine the types of training methods that need to be in the program, not the other way around.

Applying these principles is really a process of decision making. This decision making process should be guided by a series of questions:

- What are my training goals, and what types of exercises and training methods need to be applied to achieve these goals? (Principle of specificity)

- Which of these types of exercises and training methods will I be able to do based on my ability and training environment? (Principle of individuality)

- How can overload be provided to these exercises and training methods to ensure progress? (Principle of progressive overload)

- How can these exercises and methods be varied to continue to create a positive adaptation to the training program (training stimulus) without reaching the point of accommodation, where I greatly reduce my ability to adapt positively? (Principle of variation)

Properly applying the principles of specificity, individuality, progressive overload, and variation (in that order) is a proven method behind exercise program design that we can all follow. If you use this simple, principle-based decision making process as a general guideline, it can lead to the creation of fundamentally sound and well-rounded training programs that will stand the test of time.

- Harman E. The biomechanics of resistance exercise. In: Baechle, ER, and Earle, R W(eds.), NSCA's Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning. (3rd ed.) Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 25-55, 2000.