Many coaches recommend that you focus your lower-body workouts around:

- A hip dominant exercise (like the deadlift)

- A knee dominant exercise (like the squat)

- A lunging or stepping exercise (like the lunge, of course)

This is a great starting point for building a lower-body workout, but it doesn't fully represent a complete leg and hip-strengthening program. For maximal strength and development, a few other exercises should be performed weekly.

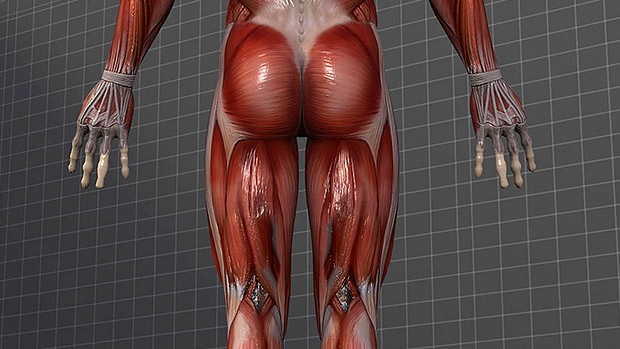

Squats, deadlifts, lunges and many variations of those exercises do a great job of loading the glutes when they're closer to a lengthened (stretched) range, but they don't do a great job of loading the glutes when they're in a shortened range.

In other words, squats, deads, and lunges create the most load on the glutes when your hips are flexed (at the bottom), but there's very little load on the glutes at the top when your hips are in extension.

Since strength is position specific, it's important to regularly perform isolation exercises such as hip thrusts, reverse hip extensions, hip lifts, 45-degree hip extensions, and 45-degree low-cable RDL's to train the glutes in the more shortened ranges of hip extension neglected by most squat, deadlift, and lunge variations.

Here are video tutorials for each of these exercises, starting with why I prefer to use single-leg hip thrusts over double-leg barbell hip thrusts.

What about cable pull-throughs? Sure, they also load the hips and glutes closer to their extended position, but due to their awkward nature, along with limited ability to continuously add progressive overload, I prefer to use the other options above.

With pull-throughs you're not limited by the weight your hips can extend against; you're limited by how much you can hold without getting pulled backward, which has much more to do with your bodyweight than your strength level!

Much has been written about hip abduction exercises like pushing your knees out against a band loop while you hip thrust or squat, lateral band walks, etc. And yes, they should be a weekly component of comprehensive lower-body program.

That said, research on professional hockey players found that they were 17 times more likely to sustain an adductor muscle strain (groin injury) if their adductor strength (muscles that move the leg toward the body's midline) was less than 80% of their abductor strength (muscles that move the leg away from the body's midline). (1)

Now, although that specific strength ratio is based on one study, a 2015 systematic review (a study of studies) found that hip adductor strength was one of the most common risk factors for groin injury in sport. (2)

In other words, an emphasis on hip abduction exercises that's not complemented with performing hip adduction exercises may put you at an increased risk of injury. This is one reason why the lower-body strength training programs I design include at least one of the following exercises to be performed each week: seated hip adduction machine, standing hip adduction, side lying hip adduction, and the Copenhagen hip adduction exercise. (Since most are familiar with how to do the adduction machine, I've omitted it in the tutorial videos.)

The Copenhagen hip adduction exercise has been shown to be a very effective movement (3,4) and it's one of my favorite exercises for targeting the hip adductors, along with the additional shoulder and torso musculature demands. Here's how I perform the Copenhagen hip adduction exercise, which is a bit different than how it's commonly done.

Some trainers may want to argue that compound and single-leg exercises like wide-stance squats, lunges, and single-leg squats train the adductors effectively enough to offset the need for doing additional adductor isolation exercises. However, the highest EMG values for the wide-stance squat (5), along with those found during a single-leg squat and a lunge, are relatively low compared to exercises that focus primarily on the hip adduction movement (6). So, with respect to reaching greater levels of muscle activity in the adductors, isolation exercises are superior to squats and lunges.

Additionally, it's important to see how the scientific evidence falls in line with the principle of specificity. Research demonstrates that strength gains are highly specific to the part of the movement one trains in, with limited transfer to the rest of the untrained ranges of the movement that may not be addressed in a given exercise (7,8).

With this in mind, exercises developed to train the hip adductors directly – such as standing hip adductions with a band or cable, the Copenhagen hip adduction exercise, and the hip adductor machine – involve moving through larger ranges of motion of hip adduction than exercises like squats, single-leg squats, and lunges. Therefore, when training the adductor musculature, it makes sense to also add such exercises into a program to train in ranges of motions that may not be sufficiently addressed by more compound exercises. (9)

Each week, include some type of focused knee-flexion exercise, such as a stability-ball leg curl (single or double leg), Nordic hamstring curl or glute-ham raise, or leg curl machine (seated or lying).

Several studies have shown that strength training programs involving the Nordic hamstring curl, which is basically the partner version of a glute-ham raise, demonstrated a significant reduction in hamstring strains incidence. (10,11,12)

The research on leg curls is also compelling. One study separated elite soccer players into two groups. Although both groups used the same training programs, one group had additional, specific hamstring training using the lying hamstring curl machine and the other did not. The results showed that the addition of the lying curl increased sprint speed and decreased the risk of suffering a hamstring strain injury. (13)

This agrees with other research, which showed that the lying leg curl (where movement originates at the knee joint) elicited significantly greater activation of the lower lateral and lower medial hamstrings compared to the stiff-legged deadlift, where movement originates at the hip joint, such as in a Romanian deadlift. (14)

The takeaway from the above research? Single-joint exercises provide a positive transfer into improved performance and injury risk reduction. But there's more.

A comprehensive hamstring program should also contain at least one exercise where movement is focused at the hip joint (such as the deadlift) and one exercise where movement is focused at the knee joint (such as the leg curl machine).

This is because different regions of the hamstring complex can be regionally targeted through exercise selection. So, each type of exercise offers unique but complementary training benefits.

That said, it makes sense that the same applies to the benefit of regularly using knee extension-based exercises like machine leg extensions or backward sled pulls, along with more multi-joint knee-oriented exercises like squats, lunges, and step-ups.

Research shows the leg extension creates much higher levels of activation in the rectus femoris compared to the squat (15), which is likely why other research shows the rectus femoris seems to grow more from single-joint, machine-based knee extension training relative to the other three quadriceps. (16)

Even if you're not motivated by that research, we can all agree that muscles respond (make strength adaptations) to how they're loaded, which is the principle of specificity.

Well, as you descend into the bottom of the squat or lunge (in hip flexion and knee flexion), the rectus femoris is trying to lengthen at the knee but shorten at the hip, and ends up staying roughly the same length. Then as you ascend (performing hip extension and knee extension), the muscle is trying to shorten at the knee but lengthen at the hip, and again ends up staying about the same length. (17)

In other words, to improve your strength in movements like backpedaling, decelerating forward momentum to change direction, or to walk down stairs or downhill, you need to train such actions. Reverse sled pulls and leg extensions are my top two options for the task.

Additionally, many of the arguments against utilizing the knee extension in healthy populations (out of concern for patella femoral joint forces and ACL health) are unfounded and logically inconsistent. (9)

Not to mention, when it comes to strengthening the quads, there's a multitude of studies showing better quadriceps strength gains (even in post ACL reconstruction patients) when combining open-kinetic chain exercises like leg extensions along with closed-kinetic chain exercises like squats and lunges over using only closed-kinetic chain exercises. (18)

What the scientific evidence says and training principles dictate is contrary to the common belief that just sticking to the "big" compound lifts provide a fully comprehensive strength training stimulus. They don't.

- Tyler TF et al. The association of hip strength and flexibility with the incidence of adductor muscle strains in professional ice hockey players. Am J Sports Med. 2001 Mar-Apr;29(2):124-8. PubMed.

- Whittaker JL et al. Risk factors for groin injury in sport: an updated systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2015 Jun;49(12):803-9. PubMed.

- Serner A et al. EMG evaluation of hip adduction exercises for soccer players: implications for exercise selection in prevention and treatment of groin injuries. Br J Sports Med. 2014 Jul;48(14):1108-14. PubMed.

- Ishøi L et al. Large eccentric strength increase using the Copenhagen Adduction exercise in football: A randomized controlled trial. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2016 Nov;26(11):1334-1342. PubMed.

- Clark DR et al. Muscle activation in the loaded free barbell squat: a brief review. J Strength Cond Res. 2012 Apr;26(4):1169-78. PubMed.

- Dwyer MK et al. Comparison of lower extremity kinematics and hip muscle activation during rehabilitation tasks between sexes. J Athl Train. Mar-Apr 2010;45(2):181-90. PubMed.

- Graves JE et al. Specificity of limited range of motion variable resistance training. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1989 Feb;21(1):84-9. PubMed.

- McMahon GE et al. Impact of range of motion during ecologically valid resistance training protocols on muscle size, subcutaneous fat, and strength. J Strength Cond Res. 2014 Jan;28(1):245-55. PubMed.

- Vigotsky A et al. Are the Seated Leg Extension, Leg Curl, and Adduction Machine Exercises Non-Functional or Risky? NSCA Personal Training Quarterly 2017 Jun;4.4:50-53.

- Arnason A et al. Prevention of hamstring strains in elite soccer: An intervention study. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2008 Feb;18(1):40-8. PubMed.

- Petersen J et al. Preventive effect of eccentric training on acute hamstring injuries in men's soccer: A cluster-randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2011 Nov;39(11):2296-303. PubMed.

- van der Horst N et al. The preventive effect of the nordic hamstring exercise on hamstring injuries in amateur soccer players: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2015 Jun;43(6):1316-23. PubMed.

- Askling C et al. Hamstring injury occurrence in elite soccer players after preseason strength training with eccentric overload. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2003 Aug;13(4):244-50. PubMed.

- Schoenfeld BJ et al. Regional differences in muscle activation during hamstrings exercise. J Strength Cond Res. 2015 Jan;29(1):159-64. PubMed.

- Ebben WP et al. Muscle activation during lower body resistance training. Int J Sports Med. 2009 Jan;30(1):1-8. PubMed.

- Ema R et al. Inhomogeneous architectural changes of the quadriceps femoris induced by resistance training. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2013 Nov;113(11):2691-703. PubMed.

- Beardsley C. Can you "just squat" for maximal leg development? Retrieved 2018 from www.strengthandconditioningresearch.com

- Treubig D. Why You Should Be Using Knee Extensions After ACL Reconstruction. Modern Manu Therapy. 2018.