In most gyms, overhead lifting is about as popular as Ann Coulter at an ACLU convention. Many people – coaches, trainers, and doctors alike – adamantly believe that overhead lifting will lead to or exacerbate shoulder problems and therefore should be avoided if you want to keep your shoulder joints healthy.

Oddly enough however, it's the bench press (the military press's more PC cousin), which seems more acceptable as an upper body pressing exercise, while overhead lifting remains fairly controversial. In this article, we'll take a "no spin" look at the controversy and the hype, and also provide some rational perspective on the very real benefits of overhead lifting. And yes, we'll even explore the risks as well.

Finally, we'll share some practical assessments and tips to help you become a better presser (in all planes of movement) while maintaining your orthopedic health and minimizing your risk of significant injury.

The most convenient way to begin our examination into this issue is to compare the two most popular strength sports: Olympic-style weightlifting and powerlifting. In making this comparison, however, we're going to examine weightlifting prior to 1972, when the standing press was one of the competitive events. (More about the removal of the press from the sport of weightlifting a bit later.)

If you spend any time looking at the scientific literature on injury statistics between these two sports, it's obvious that injuries to the lower back, knees, and shoulders do occur. The problem isn't necessarily with the specific exercises, but in the manner in which they're performed.

Frankly, any time you're maximally stressing an area (like when you're trying too hit a new PR), a certain degree of risk comes with the territory. Any activity that has the potential to change your body positively also comes with some potential for problems.

Since training always carries some degree of risk, when we prescribe programs for new or existing distance coaching clients, we always exhibit the following disclaimer at the beginning:

Disclaimer: All forms of exercise are stressful to your body!

- If the stress is insufficient, you won't hurt yourself, nor will you improve your fitness levels.

- If the stress is excessive, you may become injured.

- If the stress is optimal, you will improve your fitness levels without incurring damage to your body.

Therefore:

- If you know or suspect that you have an injury or health condition, it is your responsibility to seek qualified medical supervision and clearance before initiating any exercise program!

- If an exercise causes pain and/or swelling, discontinue immediately and consult qualified medical supervision for diagnosis and treatment.

- Always inspect exercise equipment and facilities for safety before use.

- Report damaged equipment to your health club staff where applicable.

- Charles Staley and his staff will take every possible precaution to ensure your safety; however, ultimately, you are responsible for your own well-being. If in doubt, err on the side of caution.

Much like airplane accidents, almost all non-traumatic injuries in resistance training occur due to multiple factors. What this means is that when examining an injury derived from a specific exercise, you must look at the entire situation and not just blame the specific exercise, which may simply be the "last straw" in a long chain of events.

Some useful questions to ask about any injury include:

- Was there inappropriate or excessive volume or intensity of loading?

- Was there adequate warm-up or pre-activity preparation (PAP) prior to the workout?

- Conversely, was there excessive warm-up leading to tissue fatigue prior to lifting?

- Was your technique adequate or unsafe during the lift?

- Are you using optimal breathing (breath-holding) and bracing strategies?

- Were you using a mirror?

- What type of shoes were you lifting in? This is especially relevant for squats and deadlifts, but can also impact overhead lifts.

- Were you adequately nourished or hydrated prior to and during the session?

- Were you "present" and focused, or distracted during your workout?

So ultimately, you could argue that there really are no dangerous exercises, just unhealthy, dangerous, stupid, or unsound ways of performing them. This advice is especially relevant to the overhead lifting debate because just as there are lots of lifters who have pain when lifting overhead, there are scads of others who don't. Now, about the press and weightlifting...

Up until 1972, the standing press was one of the three lifts contested in Olympic-style weightlifting. The reason the press was eliminated from competition wasn't because it was inherently dangerous for the shoulder, but because lifters were turning it into a standing bench press by leaning back excessively, putting the lumbar spine at risk and making the technique criteria difficult to enforce.

According to Artie Drechsler, author of the acclaimed The Weightlifting Encyclopedia, shoulder injuries were rare when the press was a contested exercise because, at that time, a much higher volume of overhead pressing exercises was practiced by most lifters. After the press was removed from competition, the rate of shoulder injuries began to increase. This is often attributed to the lack of adequate overhead strength and the subsequent stability you gain from doing the overhead lifts correctly.

Contrast this to the bench press, where the incidence of shoulder injury is much higher and remains one of the only exercises that yearly kills a couple of lifters who decided to bite off a little more than they could chew without a spotter. So why then is overhead lifting so maligned by coaches and trainees? There really are no simple answers but we'll begin to answer this question by looking at the anatomy...

In terms of injury potential, the shoulder-joint complex is probably more vulnerable to certain injuries because of the mobility it affords. A core principle of human anatomy is that great mobility comes at the expense of stability (and vise-versa). The shoulder joint is one of the most mobile joints in the body, but it's also one of the least stable. In fact, stabilizing the shoulder joint is like stabilizing a golf ball on a tee. In other words, the end of the upper arm bone (the humerus) is the golf ball while the golf tee is the shoulder socket (glenoid fossa). Not much of a socket, is it?

With this visual in mind, it becomes much easier to understand how this joint-complex is injured so often. (In stark contrast, the hip joint is much more stable than the shoulder joint because it has a very deep socket enveloping the head of the femur). Due to the unique nature and mobility demands of the shoulder girdle-complex, performance athletes need a high degree of "dynamic stability" which is created through coordinated muscle contraction.

Due to weak structural (bony), ligamentous, and capsular support, this dynamic support falls into the hands of several shoulder girdle, neck, and upper back muscles. The most notable and popular muscles to perform these stabilizing feats are the infamous rotator cuff (RC) muscles.

Rotator Cuff Muscles

- Infraspinatus – blue

- Subscapularis – purple

- Teres minor – yellow

- Supraspinatus – green

Although the dynamic support offered by the rotator cuff is powerful, this collective group of muscles and their associated tendons are prone to painful conditions. These problems don't usually occur overnight though. With the exception of acute traumatic injury, most shoulder problems occur over many weeks, months, or even years.

It's usually the accumulation of repeated micro-trauma that eventually leads to compromised shoulder health and subsequent rotator cuff problems. The real key then, lies in trying to prevent the problems from happening in the first place. This is obviously much easier said than done.

Some of the possible causes for shoulder pain while pressing (or jerking) overhead include: impingement syndrome, rotator cuff tear(s), anterior, posterior, or inferior capsular instability, bursitis, various tendonitis sites, excessive thoracic kyphosis, a curved or hooked acromion, scapular winging, and cervical injuries or degenerative processes with or without neurological involvement.

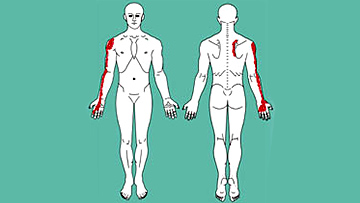

Probably one of the most frequent producers of shoulder pain is referred sensation from what are known as "myofascial trigger points." Myofascial trigger points are hyper-irritable spots located in muscle, tendon, or fascia, that when provoked, refer a noxious sensation (e.g. pain, ache, throbbing) to other, sometimes surprisingly distant parts of the body.

Trigger points in the infraspinatus muscle for example (located on the back of shoulder blade) can refer pain to the front deltoid and biceps region. If you're unfamiliar with the concept of referred pain, you'd tend to believe that the problem was located where the actual pain was being experienced. In reality, where you hurt isn't always where the actual problem is, it's just where you experience the pain.

It should be noted that trigger points usually form for protective reasons as increased muscle tone and tension can often add stability to a joint that has lost ligamentous or capsular integrity. The take-home point about trigger points is that they're alarm signals that must be removed (i.e. with massage treatment) with caution as they may be providing some protective role. The cause of why the trigger points are there in the first place must be identified or they'll just keep returning.

Probably the most common causes of shoulder pain in the athlete or casual lifter is the dreaded impingement syndrome. In this scenario, the rotator cuff tendons (most often the supraspinatus tendon) becomes entrapped under the acromion during elevation of the arm which leads to pain and weakness of the shoulder region. Of all the reasons listed above, having a genetically acquired curved (Type II) or hooked (Type III) acromion may make a lifter or athlete more vulnerable during overhead activities, butthat doesn't necessarily mean they can't be done.

Rather than fixating on a single cause, develop the ability to examine several factors and then decide how safe overhead lifting is for you. You may actually be perfectly fit to press overhead but avoid doing it based on the advice of well-meaning trainers who can't or shouldn't press overhead. As the saying goes, "If it ain't broke, don't fix it."

Another useful perspective regarding overhead pressing involves the "use it or lose it" principle. Look, if I have certain ranges of motion (known as degrees of freedom in kinesiology) in any of my joints, then I better use them. However, continuing to partake in any movement or exercise that causes consistent pain is flat-out stupid. You must investigate to see what could be going awry.

Although research shows there's little to no correlation between postural alignment and muscle strength, it's helpful to know which of your muscles might be limited in terms of mobility. Shortened muscles in one region can cause unsafe compensatory motion in other regions. Certain structures may need to be mobilized through specific massage techniques (e.g. NMT, ART, MFR) to allow adequate length for the overhead pressing motion to be performed correctly (correct motor pattern).

These tests aren't meant to be diagnostic in any way, just indicative of potential areas that may be causing problems with your shoulder mechanics. If you have a positive test (positive for tightness or shortness), mark down in the column a plus sign (+) and then make any remarks about individual differences between left and right sides in the comments section. Some of these tests are best done with a partner.

| Test | Outcome (+/-) Left or Right | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Pec Major | ||

| Pec Minor | ||

| Overhead Flexion (lats, teres major, pecs) | ||

| Subacapularis (external rotation) | ||

| Infraspinatus/teres minor (internal rotation) | ||

| Apley Scratch Test (top hand test ER; bottom hand tests IR) | ||

| Thoracic Extension Test (Arm Raise Test) * | ||

| Thomas Test (hip flexors) * * | ||

| Acromion Type (I, II, or III) * * * |

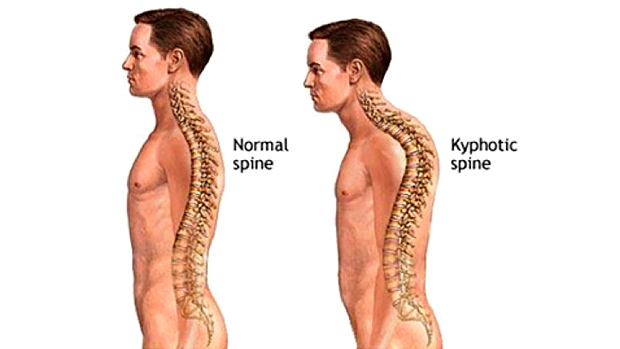

* Thoracic Extension Test – Your ability to fully flex your arms overhead is partially due to achieving almost full thoracic extension. If you're stuck in kyphosis when reaching/pressing overhead, you're almost guaranteed a shoulder impingement! The common substitution pattern in this test is lumbar hyperextension.

* * Thomas Test – Although primarily a lower extremity test, the hip flexors (ilio-psoas, TFL, and rectus femoris) can negatively affect elevation of the arm. Any tissue(s) or structures that limit overhead movement of the arms can add to an impingement scenario. This just goes to show how integrated the human body really is.

* * * Acromion Type – The only way to determine your acromion type is with an X-ray. If you've had an X-ray before of either or both of your shoulders there should be some comment about your acromion structure and type in the X-Ray Report. If you never received a report, ask your doctor to provide you a copy.

Pec Major Test

Lie supine (face up) on table with hips and knees flexed so feet are flat. Keep lower back flattened against surface to prevent compensatory lumbar extension. Beginning with the elbows facing the ceiling, slowly lower them as far as gravity will take them. For a negative test, elbows should be pointed outward with forearms flush with surface. Notice the tight left pec in second picture, which would indicate a positive test.

Pec Minor Test

Starting position is identical to Pec Major test except that arms are relaxed and directly by the sides. If one or both of the shoulders aren't in contact with the surface, suspect shortness in the pectoralis minor muscle (second picture).

Overhead Flexion Test

Starting position is same as previous test. With arms straight out in bench press position, allow arms to lower toward table without forcing them while keeping the elbow close to the ear. If the arms rest flat on the table with the elbows fairly close to the ears, then the length is normal.

If the arms can't reach the table then suspect shortness in the lats, pecs, and teres major muscles. If the elbow bends away from the ear, then the latissimus and teres major muscle are probably short. Notice the shortness in the left arm in the picture below.

Subscapularis (External Rotation) Test

In supine position, stabilize the anterior shoulder to keep the scapular from moving. Shoulder is abducted so that the humerus is in line with the sternum.

With elbow at right angle, passively externally rotate the arms until mild to moderate resistance is felt. Arm/shoulder ideally reach horizontal (parallel with the floor). Any limitation might indicate a short subscpularis muscle.

Infraspinatus (Internal Rotation Test)

Starting position is identical to subscapularis test except that now you'll attempt to internally rotate the shoulder so that the forearm lies parallel with the floor. Failure to reach the horizontal position is probably due to shortness in the infraspinatus and teres minor muscles, two of the crucial rotator cuff muscles. We find most people are short in this test, most likely due to trigger point activity in the infraspinatus muscles.

Apley Scratch Test

The top hand tests the length in muscles that internally rotate the shoulder: subscapularis, pecs, lats, and teres major. If the triceps are short they might also limit the range of motion in this test. You should be able to reach the upper angle of the opposite scapula if you have ideal range of motion.

The lower hand tests the length of the external rotator muscles: infraspinatus and teres minor. Ideally, you should be able to reach the lower angle of the opposite scapula.

Thoracic Extension (Arm Raise) Test

From a standing position, raise your arms in front of you as high as you comfortably can. Make sure that you don't arch your lower back to substitute for thoracic and shoulder range of motion.

You should be able to get your arms slightly behind your head with the thoracic spine either completely or nearly straight. If you're a crunch or sit-up king/queen you may have shortness in your rectus abdominus muscles that prevents you from fully extending your thoracic spine. Solutions: choose better trunk exercises and start stretching your dear abbies!

Thomas Test

This tests the length of the crucially important hip-flexor muscles (psoas, iliacus, rectus femoris, and tensor fascia latae). You need a treatment table or any other raised flat surface that's sturdy.

To ensure an accurate test, get your buttocks near the edge of the table to ensure that the hip joint can extend. With both legs pulled up near the chest, slowly lower one leg so that it lies as low as possible while being totally relaxed. The thigh near the chest should be hugged by your arms to ensure that the lower back stays flat against the surface you're lying on.

If the psoas muscle is of normal length, the thigh should lie parallel to the floor or slightly below. If it's higher than parallel then suspect shortness in the ilio-psoas muscles. If the rectus femoris is of normal length, the lower leg should hang straight down toward the floor with the knee bent roughly at a 90 degree angle. Abduction of the hip might indicate a shortened tensor fascia latae (TFL) muscle.

As mentioned above, the goal with these tests isn't to diagnose specific shoulder conditions and pathologies, but rather to collect data on which areas of the shoulder girdle might need some attention to improve shoulder mechanics.

With the information from the tests, you can then make more educated decisions regarding treatments that might be helpful for you. These include: various massage techniques, stretching and mobilizations by a qualified practitioner or even a foam roller, chiropractic and physiotherapeutic joint manipulations, EMS or ultrasound, Cold Laser Therapy, etc.

Probably the most popular therapeutic strategy these days is to perform so-called "corrective exercises" for the rotator cuff muscles which involve isolated joint movements. The idea is to attempt to "isolate" one or more of the rotator cuff muscles to restore its strength.

One thing that always struck us as counterproductive is that during any type of isolation exercises, you're adding unnatural stress to the muscle and its tendons. After all, in "real life" movements, the goal is to share and distribute the load among several muscles rather than trying to focus the stress on just one.

We think it goes back to our obsession for fatigue – when you isolate a muscle, you significantly increase the stress imposed upon it and then experience the glorified lactate build-up, fatigue, trembling, and finally total muscle failure if you make it that far. For those who are suffering from any kind of tendonitis in the shoulder girdle region, these isolated rotator cuff exercises might actually increase pain and inflammation to the region and make your shoulder feel worse.

In contrast, the use of PNF and spiral-diagonal patterns of movement activate multiple muscles and can serve as much more integrated rotator cuff exercises. In this fashion, you strengthen the supposedly weak rotator cuff muscles along with the other players (pecs, lats, delts, long head of biceps and triceps, traps, rhomboids, serratus muscles) so that an integrated orchestra of movement occurs that's much more functional and similar to real life movement. As the saying goes, the body knows only of movements, not muscles.

Here's a tip: there are many lifters who, despite their best efforts, continue to have pain during certain portions of the overhead pressing movement. For many of these lifters however, there's no pain when the bar is completely overhead in the support position.

For these trainees, variations of the jerk, including push jerks and push-presses, can be valuable alternatives as they help avoid the painful regions of the movement. This is a case where speed or momentum is actually safer than doing the exercise with a slow, concerted effort that's so commonly recommended by coaches and trainers. Slower isn't always better!

An additional alternative to getting the bar overhead is to perform what are known as overhead supports (or jerk recoveries) where you take a loaded barbell off the top pins in a power rack and just support the weight for one to three seconds before lowering it back to the pins. This exercise is good not only for shoulder stability but for total body conditioning. It has a trunk strengthening effect that's hard to get from typical "core" exercises.

Since this is an article about pressing, we'd be remiss if we failed to give some helpful tips on how to press in the first place. Below is a picture showing bad form and good form in the finished overhead position. If you look more like the bad form picture, you should definitely think twice about pressing overhead until you try to remedy some of the potential issues that you found in the tests listed above.

Overhead (Vertical) Pressing Derivatives

The key to pressing safely overhead is posture and tension. For those of you who routinely press strictly overhead, you know how humbling this lift can be. Here's our technique checklist for the overhead press:

- Keep your chest up and your elbows tucked by your sides, not flared out. By keeping your elbow slightly tucked in (around 45 degrees), you work more in what's known as the "scapular plane," which allows more freedom for the rotator cuff tendons to pass under the acromion.

When this technique is performed correctly, there's also some surface contact between the triceps and the lat muscles which can form a "platform" from which you can push. Anyone who knows how to bench press with more of a powerlifting "strength" technique will understand the importance of using the lats to bench; it's the same in the overhead press.

- Keep your knees straight and rigid while keeping your glutes squeezed tight and your abs braced as if someone was about to deliver you a punch to the gut. Whatever you do, don't try to perform a vacuum pose and suck in your belly button! Vacuum pose, great for bodybuilding contests, bad for pressing!

- "Keep your shoulders in their sockets!" Our good friend Pavel Tsatsouline is well known for teaching this technique to his students. It results in much less pain and improved strength when pressing overhead. One way to accomplish this is to visualize that you're pushing yourself away from the weight which will help to keep your shoulders down and minimize excessive upper trapezius involvement.

Basically, this is a way to make presses more "closed-chain," like a push-up. In the rehab world, closed-chain exercises are known to enhance joint stability because they activate muscle all around the joints in what's known as "co-contraction." This technique dramatically enhances joint stability and thus strength and safety of the movement.

- Inhale and hold your breath during most of the movement. If you breathe out during the lift, you'll decrease the intra-abdominal and intra-thoracic pressure which will decrease your shoulder stability and strength. If you must exhale during the lift, do so slowly through pursed lips. This will help maintain the pressurization throughout your abdominal and thoracic cavities and keep the lift safer.

Bench (Horizontal) Pressing Derivatives

This exercise has been covered so many times. For an excellent primer on proper bench press technique, check out Dave Tate's Bench Press 600 Pounds on this mighty lift!

The take-home message of this article is that overhead pressing is a potentially helpful or harmful activity depending on your specific body mechanics and how you perform the exercise.

We purposely left out prescriptive solutions to the common restrictions that the tests uncovered because trying to give rehabilitative advice in an article of this type is difficult at best. However, with the info you've gathered about your own body, you can now make more educated decisions regarding therapy or treatment.

Remember, most exercises aren't in and of themselves dangerous. Overhead pressing is no different. Overhead work kind of reminds us of squatting: how often have you heard someone comment on how squatting hurts their knees or back? Then, when we see them squat, we're reminded of wise words from T-Nation contributor Dan John: "No! The way you squat is bad for your knees and back!"

That's kind of how we feel about overhead work. Many lifters have never really been trained to press overhead properly since this country is so heavily focused on the bench press as the marker of gym studliness. How often do you hear two lifters conversing in a gym when ones asks the other, "How much ya overhead press?"

Overhead work offers a great stimulus to total body strength and stability and should be included in the programs of most healthy athletes. If pain and dysfunction are present, get them evaluated and see what changes can be made to allow you to press pain-free!