Tony Gentilcore, along with his business partner, Eric Cressey, look at bodies as advanced pieces of engineering. As human engineers, their primary purpose is to make each piece of "machinery" as strong as it can possibly be. (It's said, only half jokingly, that they can take someone the size of David Spade and make him lift like Dave Tate.) If the machinery needs fortification in the way of muscle, they'll systematically add it so that the shape of the machine is congruent with its function and purpose. Lastly, they want the machine to move as flawlessly as nature intended, with supreme power and fluidity. Other trainers may produce human Humvees, but Gentilcore and Cressey create human BMWs with 507 horsepower.

Become Seriously Stronger, Not Just Bigger

Let me start by saying that I'm probably going to piss off many people with this article. Or, at the very least, mildly irritate them and/or cause them not to send me a Christmas card this year.

Here's the deal: Leg curls are a waste of time. And while I'm at it, I'll also throw leg presses, pec deck flyes, those 1/4 ROM thingamabobers you call "squats," and pretty much anything using a Smith Machine under the Useless Exercise bus as well.

I'll be the first to admit that I have a biased approach to training people, and that I lean more towards the performance and "actually making people stronger" side of things – so one might understand why I'm not such a big fan of the aforementioned exercises listed above.

As luck would have it, I'm also the co-owner of my own strength and conditioning facility, so it's safe to say I live in a bubble where I'm able to control what is and what isn't done under my supervision.

Put another way, myself, Eric Cressey, as well as the rest of the CP staff oversee everything that's done under our watch. We write every program for every individual, and it's no coincidence that we don't include a "shoulders and biceps day" in any of our programs.

If you're still not picking up what I'm putting down, maybe this will clear things up: People don't do stupid shit in my gym.

Get Rid of Exercises That Don't Produce Results

I recognize that in an effort to get bigger, leaner, stronger, and/or more sexified (make girls want to hang out with you), you bust your ass in the gym five days per week. Thing is, if you're going to be honest with yourself – and I mean really honest – you look the same now as you did two years ago.

Not surprisingly, you haven't seen any improvement in [insert exercise here] in six months, and worst of all, the only "action" you've gotten lately is the Lord of the Rings marathon that's been playing on TNT for the past week.

You're using the exact same routine, with the exact same exercises, with the exact same set/rep scheme, in the exact same order, over and over and over again. It's no wonder you haven't made any progress!

Whenever I happen to train at a commercial gym, one of the biggest mistakes that I see guys making is the fact that they're not training, they're working out. Most (not all) tend to just flounder around, do a few sets of this, a couple of sets of that, watch a few highlights on Sports Center, flex in the mirror (yeah, I saw you), throw in some crunches, pound a protein shake, give each other a high five, and call it a day.

Exercises That Work

While I can appreciate that more people are moving and making a concerted effort to get better, I often have to fight the urge to stab myself in the face with a running chainsaw whenever I watch someone perform exercises that, for lack of a better term, suck.

That said, below are a handful of new (to you) exercises that I use personally, as well as with many of the clients and athletes I train.

1 – Half Kneeling Cable Anti-Rotation Press

I don't get why people are still doing crunches and sit-ups. Dr. Stuart McGill has shown repeatedly in his research that repetitive spinal flexion is the exact mechanism for disc herniations. Additionally, it's been well established that every crunch or sit-up you do places roughly 760 lbs of compressive load on your lumbar spine. Translation: OUCH!

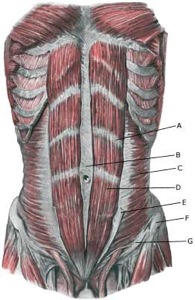

Given the work of people like Shirley Sahrmann, Gray Cook, Mike Boyle, and a lot of other people who are smarter than myself, it's pretty apparent that the "core" should be trained primarily with stability/anti-rotation in mind. For proof, just look at a basic anatomy chart on the left and it's pretty evident that this is the case.

As you can clearly see, the abdominal region is more of a crosshatched web and has muscle fibers that go vertically AND horizontally. I don't remember who I originally heard this from, but if your abs were designed specifically for flexion (think crunches and sit-ups) they'd be a hamstring.

Even more importantly, with respect to rotation, it's important to note the actual physiology of the spine. The lumbar spine isn't designed for a lot of movement; roughly 13 degrees total to be exact (0-2 degrees per segment).

Conversely, the thoracic spine is where most of the motion should come from. Here, each segment elicits 7-9 degrees per segment, totaling roughly 70 degrees of "acceptable" rotation. I only bring this up because as you can see from the video below, any rotation that does occur, occurs from the t-spine and not the lumbar spine.

Key Coaching Cues:

As of late, this has been one of my favorite "core" exercises to do with clients. It's a lot more challenging than it looks, and if you never knew where your obliques were, this exercise will let you know very quickly.

Much like half kneeling chops or lifts, you'll be using a standard cable system, albeit here you'll set up facing away from the cable machine.

You want to think about "being tall" throughout the duration of the movement. No slouching, lurch. You can scour the gym floor for loose change later. Chest up, shoulders back.

Your standing leg (the one you're not kneeling on) should be more towards the mid-line of your body, with toes pointing straight ahead. As well, you want to squeeze the glute of the kneeling leg as hard as you can (which provides a nice active stretch of the hip flexors).

It's important to keep tension in the rope the entire time; don't let the rope go slack!

Simply "press" the rope out in front of you, making sure to rotate through the chest and not the lower back. Perform all reps on one side, then switch and do the same on the opposite side.

2 – Bodysaw

So by now, it should come as no surprise when I say that a little piece of my soul dies every time I come across an article or watch the latest infomercial promoting some new product that invariably promises a firm and svelte midsection – using crunches no less.

Keeping with the above theme, people tend to pay attention whenever someone mentions the word "core," which is why I like to go out of my way to showcase exercises that train it in the most "spine friendly" and efficient way possible.

I, for one, hate planks and their variations. Sure, they have a time and place, but for all practical purposes, I'd much rather make them more challenging than make them longer. This next variation – the bodysaw – is one that I snaked from Mike Boyle, and it's a great exercise to train the anterior core; or, more specifically, anti-extension.

Key Coaching Cues:

Note: Setting up on a slideboard ( For those who don't have access to a slideboard, you could just as easily use a pair of furniture gliders), assume a plank position with your forearms on solid ground, and your toes on the slideboard (or gliders).

Brace your abs (like someone was going to hoof you in the stomach), squeeze your glutes, and try to keep your chin tucked (don't poke your head towards the ground).

From there, simply "push" yourself back through the forearms while maintaining a neutral spine throughout. This is a self-limiting exercise, so it's important to note if or when you compensate by either hiking your hips up in the air or hyperextending your lumbar spine.

Regardless, you want to stop short of either of these happening and only use your "usable range of motion." For some this may only be a few inches; for others it may be until their arms are fully extended.

To make these more challenging, you can also perform this exercise one leg at a time, or place a plate on top of the gliders for additional friction. See the video below for a demonstration.

3 – Ball-to-Wall Rhythmic Stabilizations

Giving credit where credit is due, I "stole" this exercise from Mike Reinold, who's a brilliant physical therapist here in the Boston area who also happens to be the Red Sox head athletic trainer. Since I work with a lot of baseball players, this exercise has been invaluable, but it's also a great exercise for the weekend warriors as well.

Nerd Alert

Before I get into the nitty gritty, however, let's take a few steps back and get a little geeky. If I were to ask you what's the function of the rotator cuff (see photo below), what would you say? If I were a betting man, I'd bet the farm that the vast majority of people reading this would say one of three things:

- External/Internal rotation of the arm (glenohumeral joint).

- Elevates the arm in the scapular plane.

- Ummm, uhhhh. [Crickets chirping] Isn't this the part of the article where you post a picture of a scantily clad hot chick? What the hell is the rotator cuff anyway? Is this a trick question?

If you chose either of the two former options, congratulations! You've obviously read an anatomy book within the past 25 years. But although you're technically not wrong, you're not entirely correct either.

While the rotator cuff does inevitably play a significant role in external/internal rotation, as well as elevation of the arm, you'd be remiss not to recognize that it's main function is to simply center the humeral head within the glenoid fossa, providing more dynamic stability to the joint.

As a rule, athletes (specifically overhead athletes) inherently have poor static stability and require precise interaction of the dynamic stabilizers, which coincidentally, is exactly what this exercise accomplishes.

Additionally, while I'm sure many will scoff at this exercise as being "too wimpy," and while it's certainly not as sexy as say, bench pressing with chains, I think we can all agree that shoulder health is kind of important with regard to benching big weight. Just do it, and thank me later.

Key Coaching Cues:

It's important to "pack" the shoulder down throughout the duration of the exercise. Many trainees make the mistake of shrugging and/or protracting the shoulder, which defeats the purpose entirely.

From there, all you'll do is gently move the ball in a multidirectional fashion: up, down, clockwise, counterclockwise, drawing the alphabet, etc.

Of note, while in the video below I demonstrate the exercise being done in a closed-loop (predictable) fashion, ideally this exercise would be performed with a partner lightly tapping the forearm in a more open-loop (unpredictable) fashion.

To give you an idea, I included another video below of the same exercise done in the quadruped position. Here you'll notice that you don't have to be too aggressive when pertubating (hey, get your mind out of the gutter) the arm.

Ideally this exercise can be used as some sort of "filler" in between sets of squats, deadlifts, or bench presses. Perform each position for 5-10 seconds on both arms.

4 – Anterior Loaded Barbell Step-Ups

As a coach, I like to gauge the effectiveness of any exercise by how much people hate doing it. Generally speaking, the more people hate life performing an exercise, the more benefits they're going to reap from it.

As such, my latest "go to" exercise when I want to destroy someone's day is the anterior loaded barbell step-up. As the name implies, it's simply a barbell step-up performed with the bar placed in front of the body (front squat position).

The benefits are three fold:

- It's a fantastic exercise to help build single leg strength – something I feel most (if not all) trainees need to work on.

- It activates the core significantly due to the strong anti-flexion component involved.

- It can easily be modified to the lifter. Depending on the height of the trainee, the exercise can be regressed or made harder by simply adjusting the height of the box.

Furthermore, by placing the bar on the shoulders, we're raising the center of gravity, which creates a more unstable environment. Again, we can make this easier by lowering the center of gravity and have someone use dumbbells instead (lame); or we can make it harder and have him or her hold a barbell overhead (badass).

Key Coaching Cues:

I think this one is self-explanatory. The only thing I'll add is that you want to make sure that when you step up onto the box, you do so by stepping through the heel. By doing so, you'll activate more of the glutes and hamstrings.

5 – Goblet Squat w/ Pulse

For starters, you can't discuss the goblet squat without first acknowledging the man who popularized it, Dan John.

As it is, the goblet squat is my preferred exercise when introducing the squat to new clients. Whether I'm working with a young athlete or an elderly guy with the mobility of a crowbar, the goblet squat is pretty much idiot proof, and is a superb way to groove rock-solid technique.

Of course, being an astute TNation reader, you already know this and are probably wondering how we can make it more challenging.

Lets backtrack a bit first.

For many, the lack of ability to squat to depth (in this case, anterior surface of the thighs below parallel) has often been recognized as a mobility issue.

We see this all the time when we screen athletes/clients who come into CP; we'll ask him/her to perform a simple bodyweight overhead squat, and more often than not, they're lucky to get half way down before their knees start caving in, upper back rounds over, or heels come up off the ground, to name a few.

We can argue whether it's due to poor ankle dorsiflexion, tight lats, tight hip flexors, lack of hip internal rotation, or any combination thereof, but where many miss the boat is failing to recognize that the underlying root cause could very well come down to a stability issue.

As Alwyn Cosgrove has noted in the past, the body is essentially shutting down, not because of tightness or restriction, but rather because it perceives a threat due to the lack of stability.

Got that? Cause this is where the goblet squat comes in.

By holding the dumbbell (or kettlebell) out in front of the body, the trainee is forced to engage the core, which in turn will help stabilize the body. In a matter of minutes, you can take someone with atrocious squat form and have them squatting to depth in no time flat.

The goblet squat with pulse takes all the benefits of the traditional goblet squat (grooving proper squat technique, little to no spinal loading, improving hip mobility, etc.) and adds a little flare to it. Namely, it adds another dimension to the exercise by hammering the anterior core.

Key Coaching Cues:

- Think "chest tall," and shoulder blades should be together and pointing DOWN.

- Arching your lower back as hard you can, squat down, making sure to keep the chest up and pushing your knees out to the left and right to help "open up" the hips.

- Once in the bottom position, I like to tell people to try to push their knees out with their elbows.

- From there, you'll extend your arms, pressing the kettlebell until your arms are fully extended out in front of you. Hold for a 1-2 second count, and bring kettlebell back towards the body.

- Stand up, making sure to squeeze the glutes at the top, and repeat.

That's It.

Okay, Brothers in Iron, while not an exhaustive list of exercises, these five should at some point find their way into that 3 sets of 10 loving abomination you call a workout program.

Each movement not only offers some serious bang for your training buck, they have the added bonus of possibly extending your weight training "career" in the process.

And, more importantly, they'll undoubtedly be a helluva lot more beneficial for you than leg curls.

(Waiting for the hate mail.)

Try them out today, and let me know what you think.